Zocitab vs Alternatives: Drug Comparison Tool

Select a drug to view its details.

Mechanism of Action

-

Administration Route

-

Typical Indications

-

Common Side Effects

-

Cost in the UK (2025): -

When treating colorectal cancer, Zocitab is an oral pro‑drug that converts to 5‑fluorouracil (5‑FU) in the body, offering a convenient alternative to intravenous chemotherapy. Its generic name is Capecitabine, and it’s commonly prescribed for stageIII or metastatic disease where patients need a treatment they can take at home.

Why compare Zocitab with other options?

Choosing the right regimen isn’t just about efficacy; you also weigh side‑effects, administration logistics, and cost. This guide breaks down the most frequently used alternatives, highlights where each shines, and helps you ask the right questions during a clinic visit.

Key decision criteria

- Mechanism of action: How the drug stops cancer cells from multiplying.

- Route of administration: Oral pill vs. IV infusion.

- Typical indications: Which cancer stages or sub‑types the drug targets.

- Common adverse events: Frequency and severity of side‑effects.

- Cost in the UK (2025): Approximate NHS or private price per treatment cycle.

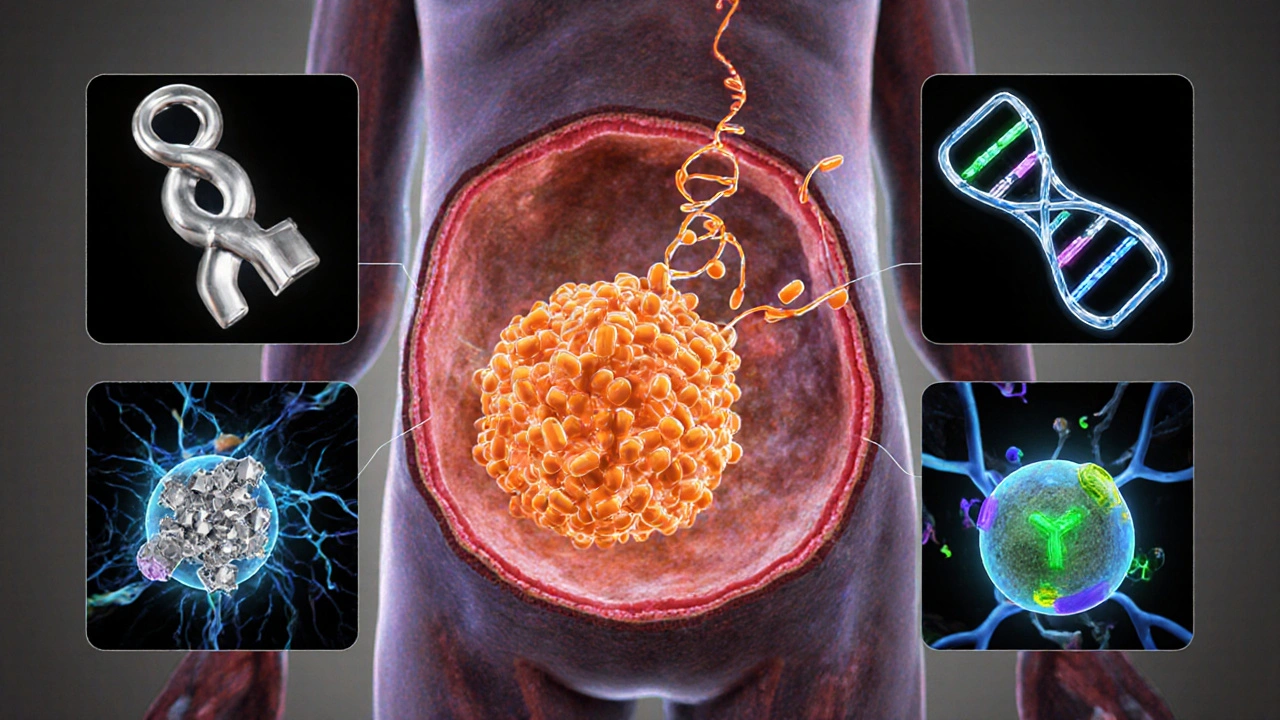

Major alternatives to Zocitab

5‑Fluorouracil (5‑FU) is the parent drug that capecitabine mimics. Delivered as an IV drip, it’s been a backbone of colorectal regimens for decades.

Oxaliplatin is a platinum‑based compound often paired with 5‑FU or capecitabine (the “CAPOX” regimen). It adds DNA cross‑linking to the mix.

Irinotecan works by inhibiting topoisomeraseI, another way to disrupt DNA replication. It’s a key component of the FOLFIRI regimen.

Trifluridine/Tipiracil (brand name Lonsurf) is an oral combination approved for heavily pre‑treated metastatic colorectal cancer.

Docetaxel is a taxane that stabilises microtubules, mainly used in breast or lung cancer but sometimes employed off‑label for gastrointestinal tumours.

Pembrolizumab is an immune checkpoint inhibitor targeting PD‑1, increasingly combined with chemotherapy for microsatellite‑instable (MSI‑H) colorectal cancers.

Colorectal cancer itself shapes drug choice; early‑stage disease may be cured with surgery plus short‑term chemo, while metastatic cases require longer, systemic control.

Comparison table

| Drug | Mechanism | Route | Typical Use | Common Side‑effects | Cost per 3‑month cycle |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zocitab | Oral pro‑drug → 5‑FU | Oral | Adjuvant & metastatic colorectal cancer | Hand‑foot syndrome, diarrhea, nausea | ≈£1,200 (NHS subsidy) |

| 5‑Fluorouracil | Pyrimidine analogue | IV infusion | Historically first‑line, often combined | Myelosuppression, mucositis | ≈£800 (IV administration costs) |

| Oxaliplatin | Platinum DNA cross‑linker | IV infusion | CAPOX regimen, metastatic disease | Peripheral neuropathy, cold‑induced paresthesia | ≈£1,500 (including infusion) |

| Irinotecan | TopoisomeraseI inhibitor | IV infusion | FOLFIRI, second‑line | Diarrhea, neutropenia | ≈£1,400 |

| Trifluridine/Tipiracil | DNA incorporation & thymidine phosphorylase inhibition | Oral | Heavily pre‑treated metastatic cases | Fatigue, anemia, neutropenia | ≈£2,200 |

| Docetaxel | Microtubule stabiliser | IV infusion | Off‑label GI cancers, breast, lung | Fluid retention, neuropathy | ≈£1,800 |

| Pembrolizumab | PD‑1 immune checkpoint inhibitor | IV infusion | MSI‑H metastatic colorectal cancer | Immune‑related colitis, rash | ≈£7,500 |

When Zocitab makes sense

Because it’s taken by mouth, Zocitab fits patients who can’t travel for frequent infusions. Clinical trials show non‑inferior overall survival to IV 5‑FU when used in CAPOX, with the added benefit of reduced hospital visits. It’s especially attractive for:

- Early‑stage adjuvant therapy after surgery.

- Patients with good performance status who prefer home treatment.

- Those with limited venous access.

However, the hand‑foot skin reaction can be a deal‑breaker for people who work with their hands a lot. Dose adjustments are common if the reaction reaches grade2 or higher.

Scenarios where an alternative might be better

If a patient has severe renal impairment, capecitabine clearance drops, raising toxicity risk. In those cases, a directly dosed IV 5‑FU regimen provides tighter control. Likewise, when a tumour shows high sensitivity to platinum agents, adding oxaliplatin (CAPOX) improves response rates compared with capecitabine alone.

For microsatellite‑instable tumours, pembrolizumab has reshaped the standard of care, delivering durable responses that oral chemotherapy can’t match. And when patients have already exhausted fluoropyrimidine‑based lines, trifluridine/tipiracil offers a new mechanism without re‑using capecitabine.

Practical tips for patients starting Zocitab

- Take with food: Reduces nausea and improves absorption.

- Stay hydrated: Aim for at least 2L daily to lower hand‑foot risk.

- Monitor blood counts: CBC every 2weeks for the first two cycles.

- Report skin changes early: Topical steroids can halt progression.

- Plan for dose holidays: If toxicity climbs, a 1‑week break often resets tolerance.

Cost considerations in the UK

The NHS generally covers Zocitab for approved indications, but private patients may face a £1,200‑£1,300 out‑of‑pocket cost per three‑month cycle. By contrast, oral trifluridine/tipiracil can be over £2,000, while immunotherapy runs into the thousands per infusion. When budgeting, also factor in travel costs for IV drugs - each infusion visit can add £30‑£50 in transport and parking.

Bottom line: How to decide

Ask your oncologist these three questions:

- Is my tumour biology (e.g., MSI status) pointing toward immunotherapy?

- Do I have kidney or liver function that might limit capecitabine?

- Can I manage the hand‑foot risk, or would an IV schedule be safer?

Answering them helps place Zocitab in the right line of therapy - either as a convenient first‑line oral option or as a component of combination regimens when paired with oxaliplatin.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can Zocitab be used after surgery for early‑stage colon cancer?

Yes. In the adjuvant setting, Zocitab (often combined with oxaliplatin as CAPOX) is a standard option to reduce recurrence risk after curative resection.

What’s the main side‑effect that distinguishes Zocitab from IV 5‑FU?

Hand‑foot skin reaction - redness, swelling, and pain on the palms and soles - is far more common with capecitabine than with IV 5‑FU.

Is dose reduction safe if I develop severe diarrhea?

Absolutely. Oncology guidelines recommend a 25% dose cut for grade2 diarrhea and a 50% cut for grade3, with a possible treatment break until symptoms improve.

How does Zocitab compare to trifluridine/tipiracil for metastatic disease?

Trifluridine/tipiracil is typically reserved after fluoropyrimidine failure. It offers a different mechanism and can work when cancer becomes resistant to capecitabine, but it’s more expensive and has a higher hematologic toxicity profile.

Are there any drug interactions I should watch for?

Capecitabine interacts with strong CYP2C9 inhibitors (e.g., fluconazole) and with anticoagulants, increasing bleeding risk. Always tell your clinician about over‑the‑counter meds and supplements.

12 Comments

When you compare Zocitab to the classic IV options the main thing is how it is taken. It comes as a pill you swallow at home. This avoids the hassle of going to a clinic for an infusion. The side‑effect that matters most is the hand‑foot syndrome which can be painful. If you have a job that uses your hands the drug may become a problem. The cost is lower than some of the newer immunotherapies but higher than plain 5‑FU. Overall the drug works well for many patients but it is not a magic bullet.

One thing to keep in mind is that oral chemotherapy shifts the responsibility to the patient. Make sure you have a clear schedule, stay hydrated, and track any skin changes early. If you notice redness on the palms or soles, use a gentle moisturizer and let your team know right away. Remember that blood work every two weeks is standard, so set a reminder on your phone. The convenience of a pill can be a real quality‑of‑life boost, especially if you live far from the hospital. And if you ever feel unwell, don’t wait – call your nurse line. This approach lets you stay active while still getting effective treatment.

It’s interesting how the guide points out the cost differences between capecitabine and newer agents. The numbers suggest that the oral drug is cheaper than immunotherapy, yet still a significant expense for private patients. The table also shows that peripheral neuropathy is uniquely linked to oxaliplatin, which might sway a patient with pre‑existing nerve issues. The emphasis on kidney function as a deciding factor makes sense because capecitabine clearance is renal‑dependent. The side‑effect filter is a handy tool for clinicians who need to match a patient’s tolerance profile. Overall the comparison feels thorough, though real‑world adherence data would add another layer.

Drama aside the facts are stark. Oral capecitabine replaces an IV drip, that’s a shift. Hand‑foot syndrome is the villain here. Dose tweaks can tame it. The drug isn’t a miracle cure but it holds its own. Patients love the convenience, the clinic loves the reduced load. Simple, effective, controversial in tone.

From a chill perspective the oral route just feels less invasive. You skip the chair at the chemo suite and can binge‑watch your shows while you take the pills. That said, staying on top of side‑effects is still key – the hand‑foot thing can sneak up on you. Hydration is your best friend, and a weekly check‑in with your nurse will keep things smooth. If you’re someone who hates needles, Zocitab is a solid alternative, especially when paired with oxaliplatin in a CAPOX regimen.

Let’s cut the crap – Zocitab is the cheap‑ass cousin of the fancy immunotherapy hype train. If you’re patriotic about our healthcare system you’ll push for this oral option because it saves the NHS some serious cash. The jargon about pyrimidine analogues and DNA cross‑linking is just pharma fluff. What matters on the ground is you can take a pill at home without the big pharma‑run infusion chairs. So stop praising the expensive IV drugs that drain wallets and embrace the home‑friendly capecitabine.

The whole comparison feels like a veil tossed over the pharma agenda. Did you notice how the cost of pembrolizumab is listed without any mention of the hidden subsidies? That’s classic. The “hand‑foot syndrome” warning is also a distraction from the deeper issue that the drug’s metabolism is manipulated by big pharma to lock patients into a cycle of side‑effect management clinics. Keep your eyes open – the data is curated to favor oral drugs only when they can be marketed as “convenient”.

While the guide is comprehensive, one could argue that the emphasis on cost ignores the real value of patient quality of life. The table neatly aligns each drug with side‑effects, yet omits the long‑term survivorship data that sometimes favors immunotherapy despite its price tag. Moreover, the recommendation to avoid Zocitab in renal impairment assumes uniform patient profiles, which is an oversimplification. In practice, individualized dosing can mitigate many of the highlighted risks. Therefore, the decision matrix should incorporate pharmacogenomic testing rather than relying solely on generic cost figures.

Hey folks, if you’re looking at the side‑effect filter, remember that hand‑foot syndrome can be managed with simple measures like cooling the palms and using barrier creams. Staying active, doing light exercises, and keeping the skin moisturised can reduce severity. Also, don’t forget your routine blood tests – they’re crucial for catching any early drops in blood counts. If you feel fatigued, talk to your doctor about a possible dose holiday; a short break often resets tolerance. Keep the conversation open with your oncology team, and you’ll navigate the treatment journey with confidence.

First, let us acknowledge that Zocitab, known generically as capecitabine, represents a pivotal shift from traditional intravenous chemotherapy to an oral administration route, which, for many patients, translates into a substantial improvement in daily convenience and overall quality of life; however, this convenience does not come without its own set of considerations, and it is essential to weigh these factors carefully. Second, the pharmacokinetic profile of capecitabine involves a three‑step enzymatic conversion to 5‑fluorouracil, a process that can be influenced by individual variations in enzyme activity, particularly thymidine phosphorylase, which is often up‑regulated in tumor tissue, thereby potentially enhancing tumor selectivity. Third, the most distinctive adverse event associated with capecitabine is the hand‑foot syndrome, characterized by erythema, swelling, and dysesthesia on the palms and soles, which can be mitigated through proactive skin care measures, dose reductions, or temporary treatment interruptions. Fourth, routine monitoring, including complete blood counts every two weeks during the initial cycles, is recommended to detect neutropenia or anemia early, ensuring timely interventions. Fifth, patients with renal impairment require dose adjustments because reduced clearance can lead to heightened toxicity; in such cases, an IV 5‑FU regimen may offer more precise dosing control. Sixth, the cost analysis presented in the guide shows that Zocitab is approximately £1,200 per three‑month cycle under NHS subsidy, a figure that, while lower than novel immunotherapies, is still significant for private patients and must be balanced against travel costs associated with intravenous infusions. Seventh, when combined with oxaliplatin in the CAPOX regimen, capecitabine demonstrates synergistic efficacy, improving response rates in metastatic colorectal cancer, albeit at the expense of cumulative neurotoxicity from the platinum component. Eighth, emerging data suggest that patients with microsatellite‑stable tumors may benefit less from immunotherapy and therefore may find capecitabine‑based regimens more appropriate as first‑line therapy. Ninth, the importance of patient education cannot be overstated; clear instructions on pill intake with food, adequate hydration, and prompt reporting of skin changes are pivotal to minimizing adverse events. Tenth, the evolving landscape of colorectal cancer treatment continues to integrate molecular profiling, and as such, the selection of capecitabine versus alternative agents should be guided by biomarkers such as KRAS, NRAS, and BRAF status. Eleventh, for heavily pre‑treated patients, trifluridine/tipiracil offers an oral alternative after capecitabine failure, though it carries a higher hematologic toxicity profile and greater cost. Twelfth, in the context of survivorship, long‑term adherence to oral therapy can be challenging, and support services, including pharmacy counseling and digital adherence tools, have shown efficacy in improving compliance. Thirteenth, clinicians should also consider the psychosocial impact of shifting from clinic‑based infusions to at‑home pill administration, as some patients may experience increased anxiety over self‑management. Fourteenth, the decision matrix presented in the guide is a valuable starting point, but individual patient preferences, comorbidities, and lifestyle factors must ultimately drive the final therapeutic choice. Finally, ongoing clinical trials continue to explore novel combinations, such as capecitabine with immune checkpoint inhibitors, which may further redefine the role of oral fluoropyrimidines in future treatment protocols.

The contrarian view in comment eight overlooks the hidden lobby behind drug pricing and that is a serious concern. It sounds like a textbook argument while ignoring the real influence of pharma on guidelines. Many clinicians aren’t aware that the cost figures are often negotiated behind closed doors. This lack of transparency definitely skews the decision‑making process. So the claim that cost alone is a simplistic metric is actually spot on because the numbers are not the whole story.

Keep the vibe positive and stay proactive about side‑effects.