When a child in Malawi needs HIV medicine, or a diabetic in Bangladesh needs insulin, the price tag isn’t just about cost-it’s about whether the drug exists at all. Behind that reality is a 30-year-old international treaty called TRIPS, which was meant to protect innovation but ended up blocking access to life-saving drugs for billions. The TRIPS Agreement is a World Trade Organization (WTO) treaty that sets minimum standards for intellectual property protection, including 20-year patents on pharmaceuticals. It came into force in 1995, and since then, it has reshaped how medicines are made, sold, and distributed across the world. The problem? It was written for wealthy countries with big drug companies-not for nations where people die because they can’t afford a pill that costs $1,000 instead of $10.

How TRIPS Changed the Global Medicine Game

Before TRIPS, countries like India, Brazil, and Thailand didn’t have to grant patents on drug products. They could copy brand-name medicines and make their own versions-called generics. In the 1990s, India produced 80% of the HIV drugs used in Africa at a fraction of the cost. A year’s supply of branded antiretroviral therapy might cost $10,000 in the U.S. In India, it cost $87. That’s not a coincidence. It’s because they didn’t have to obey patent rules.

TRIPS changed all that. Under Article 33, every WTO member had to give drug companies 20 years of exclusive rights from the date they filed their patent. That meant no one else could make the same drug, even if they had the exact formula. The result? A global shift from generic production to patent monopoly. By 2000, countries that once made their own medicines suddenly had to import them-at prices set by U.S. and European companies.

According to the World Health Organization, this shift directly contributed to 80% of the medicine access gap in low- and middle-income countries. Two billion people still lack regular access to essential drugs. And it’s not because we can’t make them-it’s because the rules say we can’t.

The Flexibility That Wasn’t Meant to Be Used

TRIPS isn’t completely rigid. It includes what are called ‘flexibilities’-legal loopholes designed to let countries respond to health emergencies. The most important one is compulsory licensing a legal tool that lets a government authorize a generic manufacturer to produce a patented drug without the company’s consent, as long as it pays fair compensation. It’s allowed under Article 31. Countries like Thailand and South Africa used it in the early 2000s to cut drug prices by 70-80%.

But here’s the catch: using compulsory licensing isn’t easy. It’s not like flipping a switch. Governments face legal threats, political pressure, and even trade sanctions. In 2006, Thailand issued licenses for three drugs-HIV, heart, and cancer medicines. The U.S. responded by removing Thailand’s preferential trade status. The cost? $57 million in lost exports per year. Brazil did the same in 2007 with an HIV drug and was put on the U.S. ‘Priority Watch List’ for two years.

Even when countries try to use the rules, they’re often outmatched. A 2017 study found that 83% of low-income countries had never issued a single compulsory license-not because they didn’t need to, but because they were afraid of the backlash. Pharmaceutical companies and their governments don’t just argue-they retaliate.

The One-Time Success Story That Proves the System Is Broken

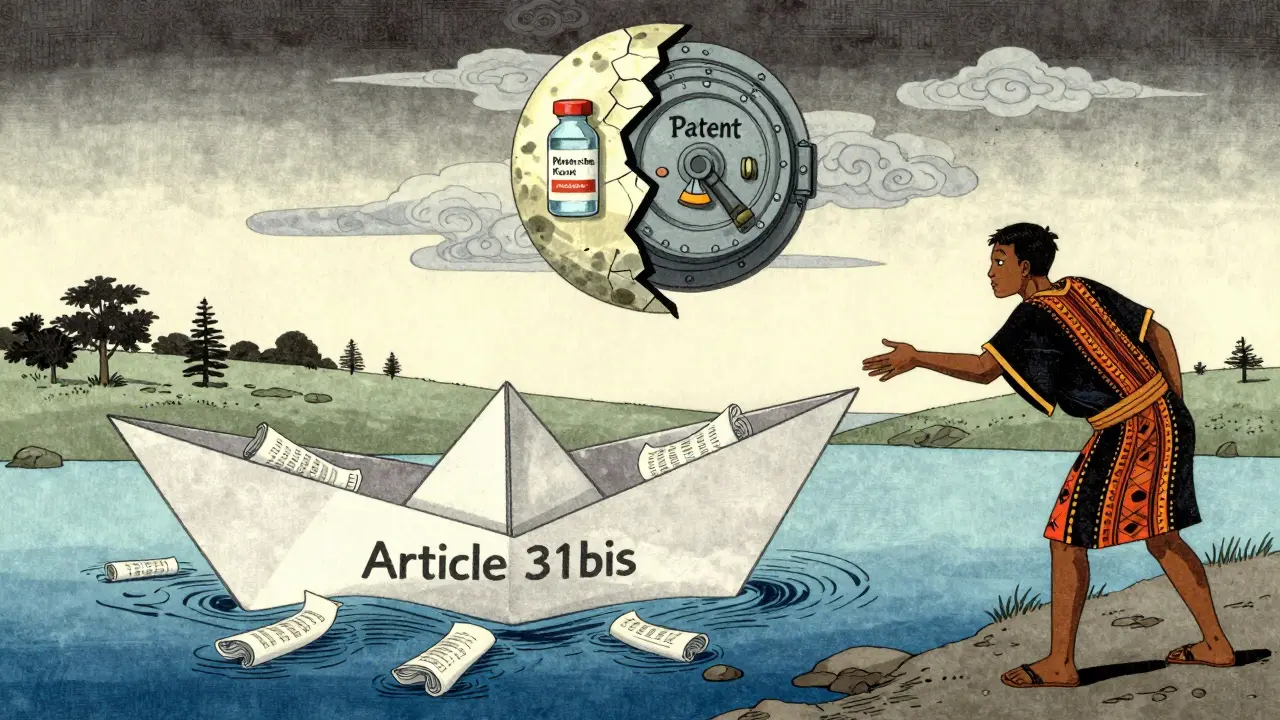

In 2007, Rwanda needed a generic HIV drug. It had no factories. It couldn’t make its own. So it turned to the one part of TRIPS meant to help countries like it: Article 31bis. This was supposed to be the fix. It lets countries without manufacturing capacity import generic drugs made under compulsory license in another country.

It took four years. Four years of paperwork, legal reviews, WTO notifications, and international negotiations. Canada’s Apotex finally made the drug. Médecins Sans Frontières helped coordinate it. Rwanda paid $1.3 million for the shipment. But even then, the price was still 30% higher than if Rwanda had been able to produce it locally.

That’s the only time Article 31bis has ever been used. Ever. Not because no one else needed it. But because the system is too slow, too complicated, and too risky. The WTO itself says the average time from request to delivery is 3.8 years. There are 78 steps involved. Most countries don’t even have a single full-time employee assigned to handle it.

TRIPS-Plus: The Hidden Rules That Make Things Worse

Even worse than TRIPS are the extra rules sneaked into trade deals. These are called ‘TRIPS-plus’ provisions. They don’t come from the WTO. They come from bilateral agreements-often pushed by the U.S., EU, or Canada. These add extra barriers: longer patent terms, restrictions on parallel imports, delays in generic approval.

For example, the U.S.-Jordan Free Trade Agreement in 2011 forced Jordan to extend patent terms beyond 20 years. That meant a drug that should have become generic in 2020 stayed expensive until 2025. A 2019 study found these extra rules cost low-income countries $2.3 billion a year in lost savings from generic competition.

And it’s not just Jordan. As of 2021, 86% of WTO members had added TRIPS-plus clauses to their trade deals. That means even if a country wants to use a TRIPS flexibility, another treaty blocks it.

What’s Changed Since COVID-19?

In October 2020, India and South Africa proposed a full TRIPS waiver for COVID-19 vaccines and treatments. They argued: if a pandemic justifies suspending patents, why not for HIV, malaria, or tuberculosis? After two years of pressure, the WTO agreed in June 2022-but only for vaccines. Therapeutics and diagnostics were left out.

The waiver allowed countries to produce and export generic vaccines without permission from patent holders. It was a win. But it was narrow. And temporary. The waiver expires in 2025 unless renewed.

Meanwhile, the Medicines Patent Pool (MPP) has licensed 44 patented medicines for generic production, mostly for HIV. But that’s only 1.2% of all patented drugs globally. And 73% of those licenses are only valid in sub-Saharan Africa-even though these diseases exist everywhere.

Drug companies say they’re doing their part. The Access to Medicine Foundation found that 7 of the top 10 pharma firms now claim to include ‘human rights due diligence’ in their strategies. But only 14% of their patented medicines are actually covered by these programs.

The Real Cost of Patent Protection

The global pharmaceutical market hit $1.42 trillion in 2022. Patented drugs make up 68% of that revenue-even though they account for only 12% of prescriptions. Generic drugs make up 89% of U.S. prescriptions. In low-income countries? Just 28%. The price difference for the same drug? Up to 1,000 times.

That’s not market competition. That’s a legal monopoly enforced by international law.

And it’s not just about money. It’s about lives. In 2023, the UNDP projected that without major reform, medicine access gaps will widen to affect 3.2 billion people by 2030. That’s nearly 40% of the world’s population.

Who’s Winning? Who’s Losing?

Pharmaceutical companies win. They get longer monopolies, higher prices, and fewer competitors. The U.S. and EU governments win. They protect their home industries and push for stronger patent rules abroad.

Who loses? The 2 billion people who can’t access essential medicines. The health workers in rural clinics who watch patients die because a pill costs $100 instead of $10. The governments that want to act but are too scared to try.

Experts are divided. Dr. Ellen ‘t Hoen, who worked for the WHO, says TRIPS flexibilities have been used more than people think-and they’ve worked. But Professor Brook Baker calls the Article 31bis system ‘fundamentally broken.’ The UN High-Level Panel on Access to Medicines didn’t mince words: ‘The TRIPS regime has institutionalized inequitable access to medicines.’

And yet, the system keeps going. Because changing it requires 164 countries to agree. And the powerful ones don’t want to.

What Needs to Change

The solution isn’t to scrap patents. It’s to fix the rules so they serve people, not profits.

- Expand the TRIPS waiver to cover all health technologies-vaccines, drugs, diagnostics.

- Make Article 31bis automatic, not bureaucratic. No 78-step process. No 4-year wait.

- Stop TRIPS-plus clauses in trade deals. They’re not trade-they’re coercion.

- Build public manufacturing capacity in low-income countries. Not just for emergencies, but for everyday needs.

- Require pharmaceutical companies to disclose R&D costs. If they say a drug costs $10,000 to develop, show the receipts.

There’s no technical barrier to making affordable medicines. We have the science. We have the factories. We have the knowledge. What we lack is the political will to change the rules.

What is the TRIPS Agreement?

The TRIPS Agreement, or Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, is a global treaty under the World Trade Organization that sets minimum standards for protecting intellectual property-including patents on medicines. It requires all member countries to grant 20 years of patent protection for pharmaceutical products, starting from the date the patent is filed.

Can countries make generic versions of patented drugs?

Yes, under specific conditions. Countries can issue compulsory licenses, allowing local manufacturers to produce generic versions without the patent holder’s permission, as long as they pay fair compensation. This is allowed under Article 31 of TRIPS. However, many countries avoid using this tool due to political pressure or fear of trade retaliation.

Why hasn’t the Article 31bis system worked?

The Article 31bis system lets countries without drug manufacturing capacity import generic medicines made under compulsory license. But it’s overly complex: it requires 78 procedural steps, takes an average of 3.8 years to complete, and involves notifying multiple international bodies. Only one country-Rwanda-has ever successfully used it, in 2012. Experts call it unworkable.

What are TRIPS-plus provisions?

TRIPS-plus provisions are extra patent protections added to bilateral trade agreements, often pushed by wealthy countries like the U.S. or EU. These can extend patent terms beyond 20 years, delay generic approval, or ban parallel imports. They make it harder for low-income countries to use TRIPS flexibilities and cost an estimated $2.3 billion in annual savings.

Did the COVID-19 TRIPS waiver solve the problem?

Partially. The 2022 WTO waiver allowed countries to produce and export generic COVID-19 vaccines without permission from patent holders. But it didn’t cover treatments or diagnostics, and it’s temporary-set to expire in 2025. It also required countries to request permission case by case, which slowed down production. Many public health advocates argue it was too little, too late.

How many people lack access to essential medicines because of TRIPS?

The World Health Organization estimates that 2 billion people worldwide lack regular access to essential medicines, and patent barriers are responsible for 80% of that gap in low- and middle-income countries. Without reform, the UNDP projects this number will rise to 3.2 billion by 2030.

What Comes Next?

The next big test is whether the WTO will act before another health crisis hits. Right now, 58 low-income countries are in trade negotiations that could lock them into more TRIPS-plus rules. The UN is calling for reform. Civil society is pushing harder. And the numbers don’t lie: patents aren’t saving lives-they’re costing them.

The truth is simple: if a drug can save a life, it shouldn’t be locked behind a patent. The law can change. It has before. It can again.