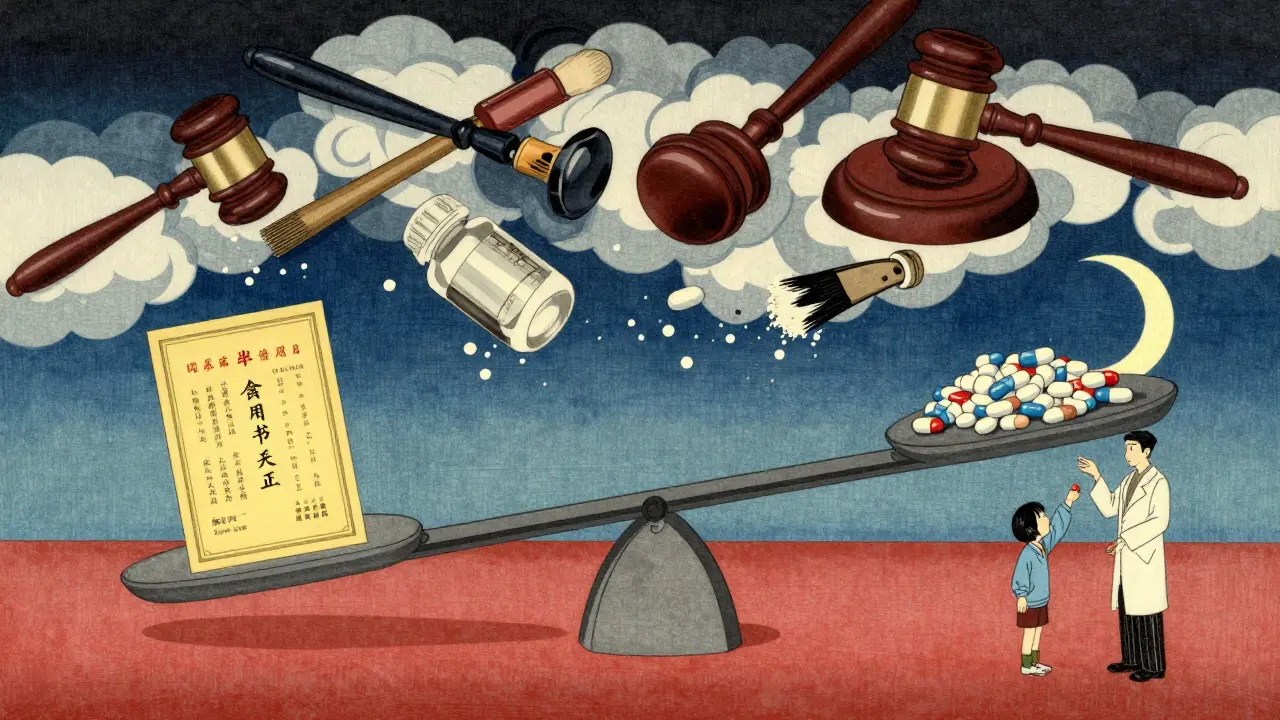

When a drug first hits the market, the company behind it gets a primary patent-usually 20 years of protection for the active chemical ingredient. But that’s rarely the end of the story. Many blockbuster drugs stay off-limits to generics for decades longer, not because of the original patent, but because of a web of secondary patents. These aren’t about the drug itself. They’re about how it’s made, how it’s taken, or what it’s used for. And they’re the main reason why some medications cost 10 times more than they should-even after the original patent expires.

What Exactly Are Secondary Patents?

Secondary patents cover everything around the active ingredient. Think of them as legal side doors. While the primary patent protects the molecule, secondary patents protect:

- Specific crystal forms (polymorphs) of the drug

- Delayed-release tablets or capsules

- A new way to take the drug-like a nasal spray instead of a pill

- A completely new medical use-for example, using a drug for cancer after it was originally approved for depression

- Combining two existing drugs into one pill

These aren’t just minor tweaks. They’re legal tools designed to reset the clock on generic competition. A 2012 study in PLOS ONE found that secondary patents added an average of 4 to 5 years of extra protection for drugs with chemical patents-and up to 11 years for drugs without them. That’s not innovation. That’s timing.

The Strategy Behind the Patents

Pharmaceutical companies don’t wait until the primary patent expires to start planning. They begin building their secondary patent network 5 to 7 years in advance. Why? Because they know generics are coming. And they want to make sure those generics can’t just slide in.

Take Nexium (a proton pump inhibitor for acid reflux). Its predecessor, Prilosec (the racemic form of esomeprazole), had its patent expire in 2001. But AstraZeneca didn’t let that stop them. They patented the single-enantiomer version-Nexium-and rebranded it as a "superior" drug. It wasn’t necessarily better for most patients. But it was new. And it came with a new patent clock. The result? Nexium became the top-selling drug in the U.S. for years, even though it was essentially the same molecule.

This is called "product hopping." And it’s common. Companies introduce a slightly modified version of their drug 1-2 years before the primary patent expires. They market it as safer, more effective, or more convenient. Then they stop making the old version. Patients and doctors are left with little choice but to switch-even if the new version costs three times more.

Who Benefits? Who Pays?

The numbers tell the story. In 2023, the top-selling drug in the world, Humira (an autoimmune disease treatment), was protected by 264 secondary patents. Its primary patent expired in 2016. But thanks to those 264 patents, generic versions didn’t arrive until 2023. During those seven years, Humira generated over $20 billion in annual revenue. That’s money that could have gone to cheaper generics.

Pharmacy benefit managers like Express Scripts say secondary patents raise drug costs by 8.3% every year. Generic manufacturers report spending $15-20 million in legal fees just to fight through one patent thicket. And patients? They’re stuck paying more for drugs that should be affordable.

But here’s the twist: not all secondary patents are bad. Some have led to real improvements. A 2021 study by the American Cancer Society found that secondary patents on new chemotherapy formulations reduced severe side effects by 37%. That’s meaningful. But those cases are rare. A 2016 Harvard study found only 12% of secondary patents delivered any real clinical benefit. The rest? They’re legal maneuvers.

How the System Works (and How It’s Being Challenged)

The U.S. system lets drugmakers list patents in the FDA’s Orange Book-a public list that tells generic companies which patents they must challenge before entering the market. But here’s the catch: only certain types of patents can be listed. Formulation and method-of-use patents? Yes. Manufacturing processes? No. That means companies file hundreds of patents-only a fraction of which show up in the Orange Book. The rest? They’re hidden. Waiting. A backup plan.

Generic companies respond with Paragraph IV certifications-legal notices that say, "We believe this patent is invalid." In 2022, 92% of listed secondary patents were challenged. But only 38% of those challenges succeeded. Why? Because courts often side with big pharma. The burden of proof is on the generic company. And the legal costs are staggering.

Global Differences Matter

The U.S. is the most permissive. But not everywhere.

In India, Section 3(d) of the Patents Act says: "You can’t patent a new form of a known drug unless it shows significantly improved efficacy." That’s why Novartis lost its battle to patent a new crystalline form of Gleevec (a leukemia drug) in 2013. India’s system lets generics enter faster. And it’s why India produces 20% of the world’s generic drugs.

Brazil and South Africa have similar rules. The European Union is tightening up too. In 2023, the European Commission said it would crack down on "patent thickets" that delay generics. The U.S. is starting to move, too. The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act gave Medicare new power to challenge certain secondary patents. It’s not a revolution-but it’s a crack in the wall.

The Future of Drug Exclusivity

Pharmaceutical companies aren’t giving up. They’re adapting. More are now combining secondary patents with data exclusivity (which protects clinical trial data for 5-12 years, even without a patent). Others are filing patents in multiple countries at once, creating global legal webs.

But pressure is building. Public opinion is shifting. Politicians are talking. Courts are getting stricter. In 2023, a federal appeals court ruled against Amgen in a major antibody patent case, signaling that overly broad claims won’t fly anymore.

By 2027, experts predict that companies will need to prove real clinical benefit-not just legal cleverness-to get secondary patents approved. That could mean fewer patents. But it could also mean better drugs.

For now, the system still favors big pharma. But the tide is turning. And for patients who’ve paid too much for too long, that’s the only change that matters.