When a hospital decides to add a new generic drug to its formulary, it’s not just about price. It’s about safety, supply, clinical outcomes, and the hidden costs no one talks about. In 2025, over 89% of all hospital drug purchases by volume are generics-but they only account for 28% of total spending. That gap tells you everything: hospitals aren’t buying cheap drugs. They’re buying the right cheap drugs. And the system they use to pick them is more complex than most people realize.

What a Hospital Formulary Really Is

A hospital formulary isn’t a static list. It’s a living, breathing decision engine. Every drug on it has been reviewed, debated, and approved by a Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) committee-usually made up of pharmacists, physicians, and sometimes nurses. These committees meet monthly or quarterly. They don’t just look at the label. They dig into bioequivalence studies, check for supply chain risks, and weigh how a drug behaves in a real hospital setting-where patients are on IVs, in ICUs, or recovering from surgery. The formulary is typically closed or partially closed. That means if a drug isn’t on the list, doctors can’t just prescribe it. They need special approval. This isn’t about control. It’s about consistency. In a retail pharmacy, a patient can pick up any brand or generic. In a hospital, a nurse administers the drug. A pharmacist checks the dose. A monitor tracks the effect. If two different versions of the same drug behave differently in a patient’s bloodstream, it can mean the difference between recovery and crisis.How Generics Make It Onto the List

Just because the FDA approves a generic doesn’t mean a hospital will use it. The FDA says it’s equivalent. The hospital needs proof it’s safe in practice. P&T committees use three filters:- Efficacy-Does it work as well as the brand? Not just in a lab, but in real patients with kidney failure, liver disease, or sepsis?

- Safety-Are there hidden differences in absorption, stability, or delivery? A generic inhaler might look identical, but if the particle size changes, it won’t reach the lungs the same way.

- Cost-Not list price. Net price. After rebates, discounts, and service fees from manufacturers.

Tiers, Trade-offs, and Hidden Costs

Most hospital formularies use a tier system:- Tier 1: Preferred generics. Lowest cost, highest use.

- Tier 2: Non-preferred generics or preferred brands. Moderate cost-sharing.

- Tier 3: Non-preferred brands. Higher cost, requires prior authorization.

- Tiers 4-5: Specialty drugs. Often not generics. High coinsurance.

Why Hospitals Don’t Just Pick the Cheapest

Retail pharmacies and Medicare Part D plans operate under different rules. Medicare must include at least two drugs in 57 therapeutic categories. Hospitals don’t have that requirement. They can-and do-limit choices to reduce risk. A hospital doesn’t care if a patient can afford a $500 monthly pill. It cares if a nurse can safely administer a $2 generic IV drip without causing a drop in blood pressure. It cares if the drug stays stable in a refrigerator for 72 hours. It cares if the vial has a tamper-proof seal. That’s why the selection process is so slow. A new generic must be submitted with an AMCP dossier-a 30-50 page document with clinical trials, pharmacology data, economic modeling, and real-world usage reports. Only 37% of hospitals have automated alerts in their electronic health records to flag non-formulary prescriptions. The rest rely on pharmacists to catch errors. That’s how mistakes happen.

Success Stories and Systemic Risks

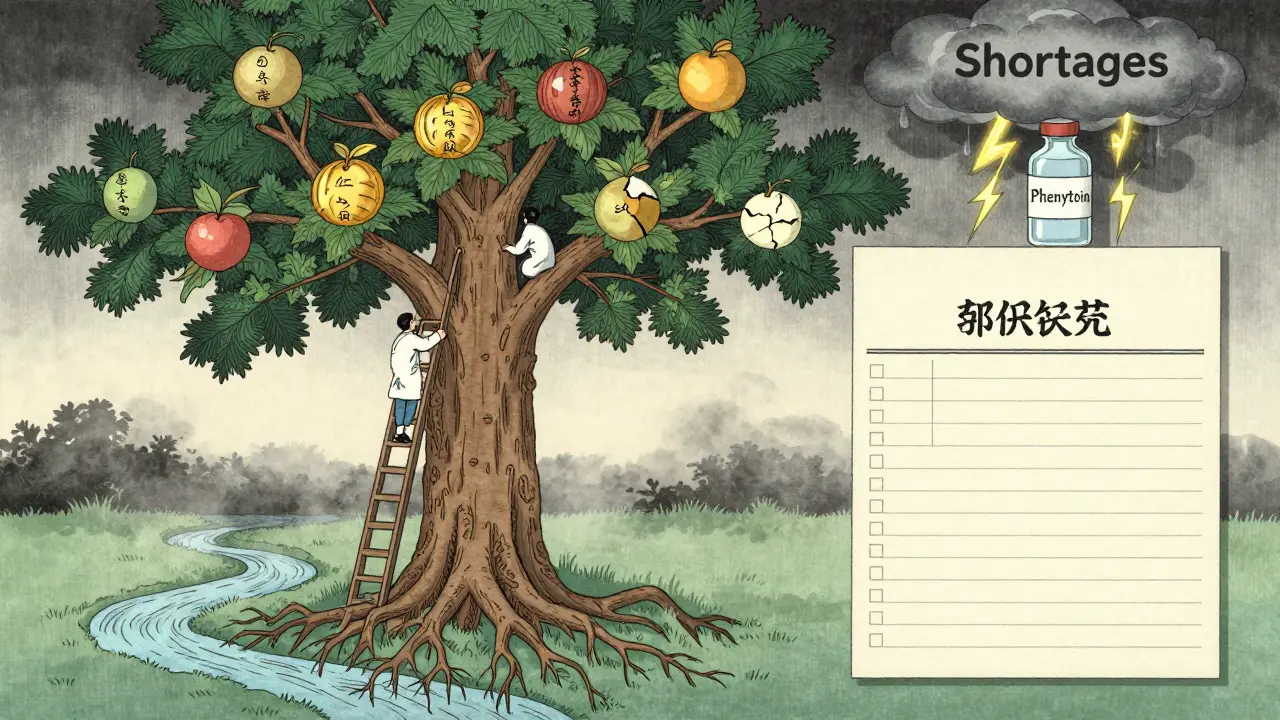

Mayo Clinic saved $1.2 million a year by switching to generics for cardiovascular drugs-after setting up a therapeutic interchange program. They didn’t just swap pills. They trained staff, updated monitoring protocols, and tracked outcomes for six months. Only then did they fully transition. Cleveland Clinic cut generic acquisition costs by 18.3% without harming patient outcomes. Their secret? A dedicated team that reviewed every new generic against clinical data, not just price tags. But the risks are growing. The FDA reported 298 active generic drug shortages in November 2023-the highest since tracking began. Most come from overseas manufacturers with thin supply chains. The 340B Drug Pricing Program lets certain hospitals buy generics at deep discounts, but it’s created a two-tier system: some hospitals get cheaper drugs, others don’t. And now, new rules are coming. The 2023 Consolidated Appropriations Act requires full transparency in generic pricing by January 2025. That means hospitals will finally see what rebates manufacturers are hiding. It could shake up the entire system.What’s Next for Hospital Formularies

The future of formulary economics is getting smarter-and more complicated. - Pharmacogenomics: 28% of academic hospitals now consider a patient’s genetic profile when choosing generics for drugs like warfarin or clopidogrel. One dose doesn’t fit all. - Value-based contracts: 47% of large hospitals now tie payments to outcomes. If a generic doesn’t reduce readmissions, the manufacturer pays back part of the cost. - Complex generics: The FDA’s GDUFA III program is investing $4.3 million a year to speed up approval of hard-to-make generics-like complex inhalers and injectables. That could fill critical gaps by 2026. But the biggest challenge remains: balancing cost with control. Hospitals need to save money. But they can’t afford to gamble with patient safety. The best formularies don’t just pick the cheapest drug. They pick the most reliable one. The one with the best track record. The one that won’t disappear next month. And the one that works-every time-in the hands of a tired nurse at 3 a.m.Why can’t hospitals just use any generic drug approved by the FDA?

FDA approval means a generic is chemically equivalent to the brand, but not necessarily clinically identical in every setting. In a hospital, drugs are given intravenously, to critically ill patients, or in combination with other meds. Small differences in absorption, stability, or delivery can cause serious side effects. P&T committees require real-world evidence-not just regulatory paperwork-to ensure safety.

Do hospital formularies prioritize cost over clinical quality?

Not ideally, but pressure to cut costs sometimes pushes decisions in that direction. Many hospitals now use net cost (after rebates), not list price, to evaluate generics. Still, 2021 ASHP research warned that rebate-driven decisions can lead to choosing drugs with poor supply chains or hidden risks. The best committees balance cost with safety, reliability, and clinical outcomes.

What’s the difference between a hospital formulary and a retail pharmacy formulary?

Hospital formularies are closed and controlled. They focus on administration by staff, not patient self-management. Retail formularies are open and incentivized-patients pay more for non-preferred drugs. Hospitals don’t care about patient copays. They care about nurse workload, drug stability, and whether a drug works in a patient with organ failure. Retail formularies also follow CMS rules requiring multiple options per drug class; hospitals don’t.

How do hospitals handle generic drug shortages?

When a generic shortages, hospitals often turn to non-formulary alternatives, which cost 3-5 times more. Some create emergency protocols to switch to brand-name drugs temporarily. Others rely on backup manufacturers or regional drug banks. But with 298 active shortages in late 2023, many hospitals are building more flexible formularies with multiple approved options for critical drugs.

Is pharmacogenomics changing how generics are chosen?

Yes. For drugs with narrow therapeutic windows-like warfarin, clopidogrel, or certain antidepressants-genetic differences affect how patients metabolize them. Twenty-eight percent of academic hospitals now use genetic testing data to guide generic selection. One patient might need a brand-name version because their genes break down the generic too quickly. This moves formulary decisions from population averages to personalized care.