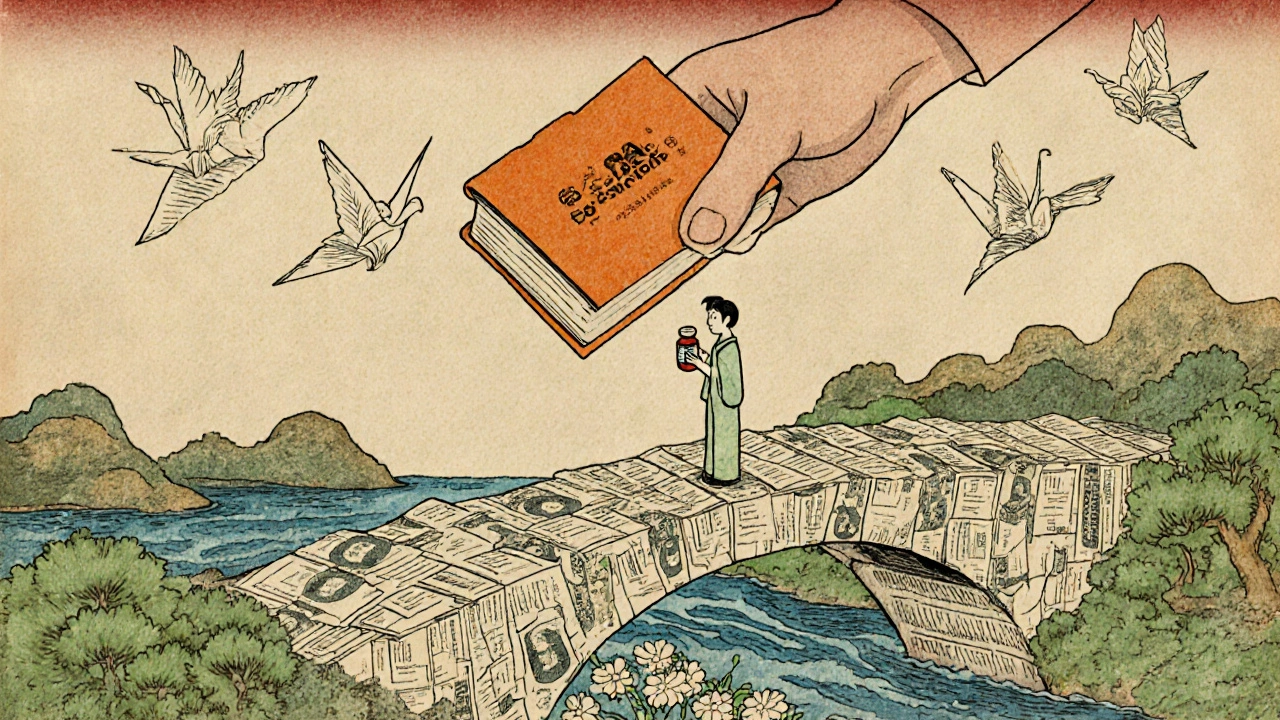

When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you’re not just saving money-you’re benefiting from a decades-long legal battle fought in courtrooms across the U.S. These aren’t abstract legal theories. They’re real decisions that decide whether a life-saving drug costs $5 or $500. The system is built on generic patent law, and a handful of landmark court rulings have reshaped how drugs reach the market.

How Generic Drugs Break Patent Monopolies

The foundation of all this is the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984. It was designed as a compromise: give brand-name drug makers extra time to recover research costs, but create a clear path for generics to enter after patents expire. The key? The Paragraph IV certification. When a generic company files an application to sell a cheaper version of a drug, they must state that the existing patent is either invalid or won’t be infringed. That single statement triggers a lawsuit from the brand-name company-and often, a 30-month delay in the generic’s release. This isn’t just paperwork. It’s a legal trigger. If the generic wins, they get 180 days of exclusive market access before other generics can jump in. That’s why companies race to be first. But winning isn’t easy. The brand companies have deep pockets and a playbook built on patents that are sometimes thin, vague, or even misleadingly listed.Amgen v. Sanofi: The End of Overly Broad Biologic Patents

In 2023, the Supreme Court handed down a decision that sent shockwaves through the biotech industry: Amgen v. Sanofi. Amgen held a patent on a class of cholesterol-lowering drugs, claiming protection for “millions” of possible antibody variations-yet only tested 26 of them. The Court said that wasn’t enough. A patent can’t cover everything you *might* invent. It has to actually enable others to make and use what’s claimed. This ruling crushed the strategy of filing broad patents on biological drugs-where small changes in protein structure can create new effects. Before this, companies would list dozens of potential variations in a patent, hoping to block every possible competitor. Now, they need to prove their claims work across the entire scope. The result? More than 40% of pending biologic patent applications in 2024 were rejected or narrowed by the USPTO, according to Federal Circuit Bar Journal data. For generic makers, this was a win. It cleared the way for biosimilars-generic versions of complex biologic drugs-to enter the market faster. For patients, it means cheaper insulin, rheumatoid arthritis treatments, and cancer therapies could become available sooner.Allergan v. Teva: Protecting the First-to-File Advantage

In 2024, the Federal Circuit ruled in Allergan v. Teva that a patent filed later can’t be used to invalidate an earlier one-even if the later patent expires first. This sounds technical, but it’s about control. Brand companies were trying to use newer, narrower patents to block generic entry, even when the original patent had already expired. The court said no. The first patent listed in the Orange Book-the official FDA directory of protected drugs-controls the timeline. If a company wants to delay generics, they need to list the *right* patent at the *right* time. This decision shut down a common tactic called “patent thicketing,” where companies pile on dozens of minor patents to confuse and exhaust generic challengers. Teva, the generic giant, had been stuck in litigation for years over a nasal spray drug. After this ruling, their product cleared the path and hit the market within six months. The FTC called it a “critical reset” for fair competition.Amarin v. Hikma: When Marketing Becomes Infringement

Here’s a twist: sometimes, a generic drug isn’t infringing on a patent-but its marketing materials are. In Amarin v. Hikma, Amarin’s drug was approved only for treating high triglycerides. But Hikma’s generic packaging and website suggested it could also treat high cholesterol-an unapproved use. The court ruled this was “induced infringement.” Even though the pill itself was legal, the way Hikma marketed it encouraged doctors to prescribe it for off-label uses covered by Amarin’s patent. The case ended in a $135 million settlement. This is now a major tool for brand companies. In 2023, 63% of induced infringement claims succeeded in federal court, according to PTAB statistics. Generic makers now spend months reviewing every word on their labels, websites, and sales brochures. One company told me they hired a former FDA compliance officer just to review their marketing copy.

Why This Matters to You

These cases aren’t just for lawyers. They affect your wallet. When a generic drug enters the market, prices drop 80-85% within a year, according to FTC data. A 30-month delay in a single drug can cost patients tens of thousands in out-of-pocket expenses. One Reddit user shared that their insulin alternative was blocked for 22 months due to patent litigation-costing them $8,400. The system is designed to balance innovation and access. But the line is thin. Brand companies use every legal tool to stretch monopolies. Generics use every loophole to get in faster. Courts are now stepping in to stop the worst abuses. The data is clear: patent litigation delays cost the U.S. healthcare system over $127 billion in potential generic savings between now and 2026, according to Evaluate Pharma. Cardiovascular and cancer drugs are the most affected. If you or someone you know takes a daily pill for heart disease, diabetes, or cancer, the timing of generic entry could mean the difference between treatment and abandonment.What’s Next?

The FDA is pushing for stricter rules on what patents can be listed in the Orange Book. Their 2025 draft rule would require companies to prove a patent is directly tied to the drug’s approved use-not just any related invention. This targets “evergreening,” where companies file patents on minor changes like pill color or dosage timing just to extend exclusivity. Meanwhile, biosimilars are rising. In 2024, 27% of patent challenges involved biologics. By 2027, that number could hit 31%. That’s good news for patients, but it means more complex litigation. Biologics aren’t simple pills-they’re living molecules made in labs. Patents on them are harder to challenge, and courts are still figuring out the rules. The Federal Circuit is also seeing more cases where patents are invalidated after being listed in the Orange Book. In 2023, 18% of patents used to block generics were later found invalid by the Patent Trial and Appeal Board. That’s a growing risk for brand companies.How Generic Manufacturers Play the Game

To get a generic drug approved, a company must file an ANDA-Abbreviated New Drug Application. But the real work happens before that. They spend months analyzing every patent listed in the Orange Book. They check if the patent is even valid. They look for loopholes. They file for inter partes review (IPR) at the PTAB, a faster, cheaper way to challenge patents than district court. In 2024, 92% of ANDA filers used IPR as part of their strategy. That’s up from 45% in 2018. It’s changed the game. Companies now hire teams of patent attorneys, regulatory experts, and pharmacokinetic scientists just to prepare one application. The cost? Around $1.2 million per product, according to Teva’s legal team. Small generic firms can’t afford it. That’s why the market is dominated by a handful of big players: Teva, Mylan, Sandoz, and Sun Pharma. The barrier to entry is now legal, not just technical.

Where the System Still Fails

Despite progress, the system is still broken in places. Some companies list patents that have nothing to do with the drug’s active ingredient-just packaging or manufacturing methods. The FDA’s Orange Book is supposed to prevent this, but it’s outdated and hard to navigate. Industry surveys give it a 3.2 out of 5 for usability. And then there’s the “product hopping” tactic. A brand company slightly changes a drug-say, switching from a tablet to a capsule-and files a new patent. Then they stop selling the old version. Patients are forced to switch, and generics can’t enter until the new patent expires. Courts have struggled to stop this, and it’s still common. The FTC says it’s cracking down. In 2024, they issued a policy statement vowing to challenge “improper patent listings.” But enforcement is slow. It takes years to investigate, and by then, the damage is done.What Patients Can Do

You can’t change the law. But you can stay informed. If your generic drug isn’t available, ask your pharmacist: “Is there a patent dispute holding it up?” They often know. If the answer is yes, check the FDA’s website for updates on the drug’s status. Some delays are temporary. Talk to your doctor about alternatives. Sometimes, another drug in the same class has already gone generic. Or ask if a mail-order pharmacy can source a version from another country where the patent has expired. And if you’re paying hundreds a month for a drug that should be cheap, speak up. Patient advocacy groups are pushing Congress to cap patent litigation delays. Your voice matters.What is the Hatch-Waxman Act and why does it matter for generic drugs?

The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 created the legal framework for generic drugs to enter the U.S. market. It lets generic companies file abbreviated applications (ANDAs) without repeating expensive clinical trials. In return, they must challenge existing patents through Paragraph IV certification, which can trigger lawsuits. The law balances innovation by giving brand companies extra patent time, while guaranteeing generics a faster, cheaper path to market-especially with a 180-day exclusivity period for the first filer.

What is the Orange Book and how does it affect generic drug approval?

The Orange Book is the FDA’s official list of approved drug products with their patent and exclusivity information. Generic manufacturers must review it before filing an ANDA. If a patent is listed, they must certify whether it’s invalid, unenforceable, or won’t be infringed. If they claim invalidity (Paragraph IV), the brand company can sue, triggering a 30-month stay on generic approval. Accurate Orange Book listings are critical-misleading or irrelevant patents can be challenged in court, but many still slip through.

What is a Paragraph IV certification?

A Paragraph IV certification is a legal statement made by a generic drug applicant asserting that a patent listed in the Orange Book is either invalid or will not be infringed by the generic product. This triggers a 45-day window for the brand company to sue for infringement. If they do, the FDA can delay approval of the generic for up to 30 months. It’s the main legal trigger for patent litigation in the generic drug industry-and the reason so many lawsuits happen.

Why do some generic drugs take years to become available after a patent expires?

Even after a patent expires, generics can be delayed by litigation. Brand companies often file multiple patents, some covering minor changes, and sue generic makers who challenge them. The 30-month stay from a Paragraph IV lawsuit can push approval years past the original patent expiry. In 2023, the median Hatch-Waxman litigation lasted 28.7 months. Some cases drag on longer due to appeals or complex biologic patents. The result? Patients pay brand prices for years longer than they should.

Can a generic drug be blocked even if the patent is invalid?

Yes. A generic drug can be blocked even if the patent is later found invalid. The 30-month stay is automatic once a lawsuit is filed under Paragraph IV. The FDA can’t approve the generic until the stay ends-whether the patent is proven valid or not. That’s why many generic companies file for inter partes review (IPR) at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board early in the process. If the patent is invalidated there, it can end the litigation and lift the stay faster than a district court trial.

15 Comments

This whole system is a joke. They patent the color of the pill and act like it's a miracle.

In India, we know what this feels like. My father waited three years for his blood pressure medicine to go generic. Three years. Meanwhile, the same drug costs less than $2 in Bangladesh. The law isn't broken-it's rigged for profit, not people.

The FDA is complicit. The Orange Book is a political tool disguised as regulatory policy. You think this is about innovation? No. It's about corporate capture. The same people who wrote the Hatch-Waxman Act now sit on pharma boards. This isn't capitalism-it's feudalism with lawyers.

There's hope though. The Amgen v. Sanofi decision? That was a real win. It means the courts are starting to see through the fluff. Keep pushing. Every time a patent gets invalidated, someone gets to breathe a little easier.

i read this and was like... wait so the generic drug is fine but if they say 'also good for cholesterol' they get sued?? like... what??

Let me be clear: America invented modern pharmaceuticals. We fund the R&D. And now we’re being punished for it by foreign governments and lazy generic manufacturers who don’t understand the cost of innovation. This isn’t justice-it’s theft disguised as affordability.

The structural inefficiencies in the Orange Book are non-trivial. The lack of real-time synchronization between USPTO filings and FDA listings creates systemic friction. This results in suboptimal market entry timing and increases litigation arbitrage opportunities for brand-name entities leveraging secondary patent thickets.

It’s funny how we call it 'patent law' but it's really just a game of chess where the pieces are molecules and the board is the courtroom. The real players? They don't even show up. They just hire people to fight for them.

I've been following this for years. The data is irrefutable: 80-85% price drops after generic entry? That’s not market dynamics-that’s proof that the original pricing was always a scam. And the 30-month stays? That’s corporate extortion with a judge’s signature on it. 🤬💉💊

Nigeria can't even get these drugs on time because of these stupid patent games. Why should Americans get cheap insulin while my sister dies because she can't afford the branded version? This isn't law-it's colonialism with a patent number.

The inter partes review (IPR) mechanism is underutilized by smaller firms due to high upfront costs. But strategically, it's the most efficient path to invalidate weak patents-faster than district court, less expensive than full litigation. The 92% adoption rate among ANDA filers in 2024 confirms its efficacy.

I just want to say… thank you… for writing this… it’s so important… people don’t realize… every time a generic comes out… someone… gets to live… longer… and that… matters…

Let’s be real. The whole system is a Ponzi scheme built on fear. Brand companies don’t innovate-they litigate. They don’t cure diseases-they delay competition. They don’t save lives-they profit from suffering. And the courts? They’re just the accountants. This isn’t healthcare. It’s a casino where the house always wins, and the patients are the ones losing their life savings.

The FDA’s 2025 draft rule is a step. Not perfect. But progress.

You say the courts are stepping in? That’s only because the public outcry reached critical mass. The moment the headlines fade, the lobbying resumes. Don’t mistake reaction for reform.