Steroid Safety Calculator

This tool helps determine if you need a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) while taking corticosteroids based on current medical evidence. It's based on findings from major studies showing corticosteroids alone don't significantly increase ulcer risk.

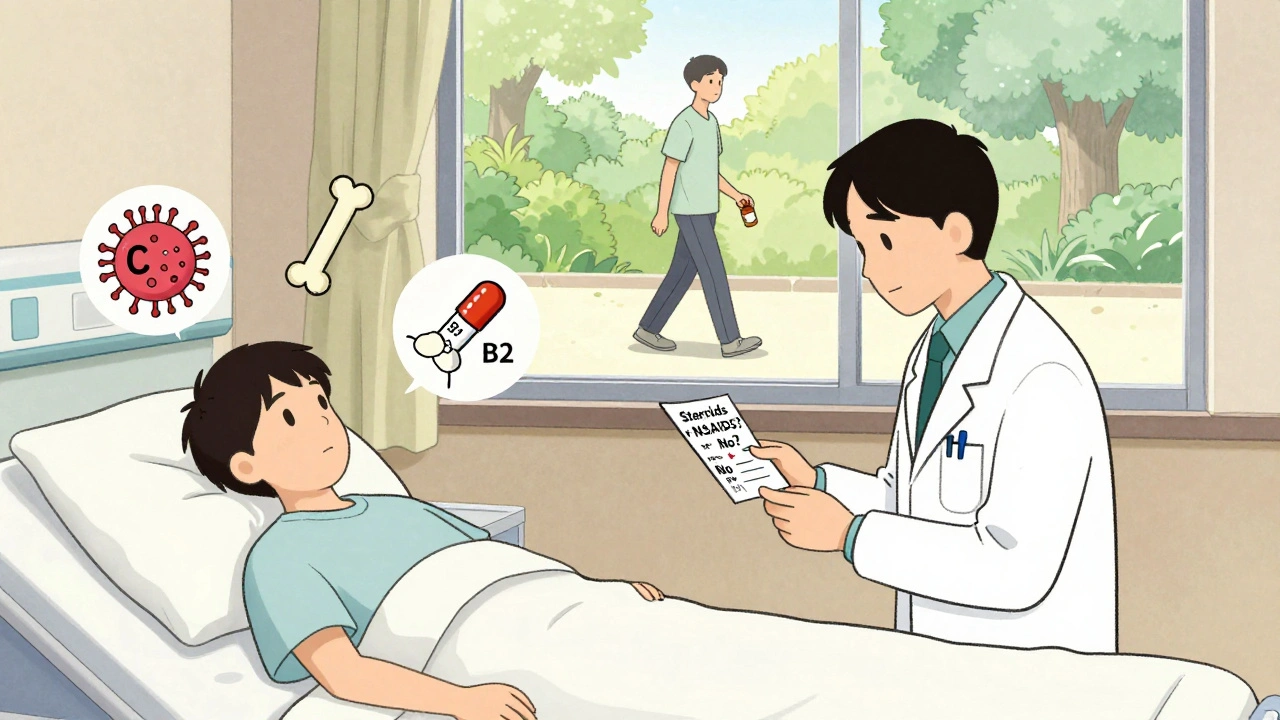

For years, doctors have been told to give proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) to anyone on corticosteroids-just to be safe. But what if that’s not helping at all? What if it’s doing more harm than good? The truth is, corticosteroids alone don’t cause gastric ulcers the way we thought. And giving PPIs to every patient on steroids might be one of the most common medical practices that’s not backed by evidence.

Why We Thought Corticosteroids Cause Ulcers

Corticosteroids like prednisone, dexamethasone, and methylprednisolone are powerful anti-inflammatory drugs. They’ve been used since the 1940s to treat everything from asthma to rheumatoid arthritis. For decades, doctors assumed they damaged the stomach lining the same way NSAIDs do-by reducing protective mucus and increasing acid. That logic made sense. So the standard became: high-dose steroid? Give a PPI. But here’s the problem: the science never supported it. A major 2013 review in Allergy, Asthma & Clinical Immunology looked at dozens of studies and found no increased risk of peptic ulcers in people taking corticosteroids alone. Even at high doses-like 60mg of prednisone daily-ulcer rates stayed around 0.4% to 1.8%. That’s lower than the rate of ulcers in people taking no medication at all in some populations. So why did we keep doing it? Because symptoms are misleading. Steroids can cause stomach discomfort, bloating, or nausea. Patients feel it. Doctors see it. They assume it’s an ulcer forming. But those symptoms often don’t mean tissue damage is happening.The Real Danger: When Steroids Meet NSAIDs

The real risk doesn’t come from steroids alone. It comes from stacking them with other drugs. A study of Medicaid patients showed that when corticosteroids are taken with NSAIDs like ibuprofen or naproxen, the risk of a gastric ulcer jumps by 4.4 times. That’s not a small increase. That’s dangerous. And it’s the only scenario where the evidence clearly supports protective treatment. Why? NSAIDs directly attack the stomach’s protective lining. Corticosteroids don’t do that. But they do slow down healing. So if an NSAID creates a tiny tear in the stomach wall, steroids make it harder for the body to fix it. The result? A bigger ulcer. A bleed. Maybe even a perforation. This is why guidelines from the American College of Gastroenterology don’t recommend PPIs for steroid users unless they’re also on NSAIDs. Or unless they have a history of ulcers. Or if they’re on blood thinners like warfarin or apixaban. Those are the real red flags.What About Hospitalized Patients?

Here’s where things get complicated. A 2014 review in BMJ Open found that hospitalized patients on corticosteroids had a 43% higher risk of GI bleeding. But outside the hospital? No increase at all. Why the difference? Hospitalized patients are often sicker. They might be on multiple drugs. They might be NPO (nothing by mouth). They might have sepsis, trauma, or organ failure-all of which independently raise bleeding risk. In that setting, steroids might be just one factor in a storm of other dangers. So if you’re admitted to the hospital and put on high-dose steroids? Yes, your doctor might still give you a PPI. But it’s not because of the steroid alone. It’s because you’re in a high-risk environment. In outpatient settings-where most people take steroids for arthritis, lupus, or COPD-the risk is so low that the benefits of a PPI don’t outweigh the downsides.

Why PPIs Aren’t Harmless

PPIs like omeprazole, pantoprazole, and esomeprazole are widely used. But they’re not harmless. Long-term use is linked to:- Increased risk of C. difficile infection

- Lower absorption of magnesium, vitamin B12, and calcium

- Higher chance of bone fractures in older adults

- Rebound acid hypersecretion when you stop them

What Should You Actually Do?

If you’re prescribed corticosteroids, here’s what matters:- Ask if you’re also taking an NSAID. If yes, you likely need a PPI. If no, you probably don’t.

- Check your history. Have you had a gastric ulcer before? Are you on blood thinners? If yes, talk to your doctor about protection.

- Don’t assume stomach pain means an ulcer. Steroids can cause bloating, gas, or nausea without damaging your stomach. Don’t rush to ask for a PPI unless symptoms are severe or bloody.

- Watch for alarm symptoms. If you vomit blood, pass black tarry stools, feel dizzy, or become pale and weak-get help immediately. These are signs of bleeding, not just irritation.

- Ask about H. pylori. This bacteria causes most ulcers. If you’ve never been tested, ask your doctor. Treating it is more effective than any PPI.

Monitoring: What to Track and When

There’s no official checklist for monitoring steroid-induced ulcers because the risk is so low. But smart monitoring is still important:- At start: Review all medications. Flag NSAIDs, anticoagulants, SSRIs. Test for H. pylori if you have a history of GI issues.

- At 1-2 weeks: Note any new stomach pain, nausea, or appetite loss. Don’t panic-but don’t ignore it either.

- At 1 month: Check for signs of anemia (fatigue, pale skin, shortness of breath). A simple blood test can catch slow bleeding before it becomes serious.

- Every 3-6 months: If you’re on long-term steroids, get your blood sugar checked. Steroids raise glucose levels, especially after meals. This is far more common than ulcers.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Matters

This isn’t just about one drug. It’s about how medicine works-and sometimes doesn’t work. We’ve been giving PPIs to steroid patients for decades because it felt right. Because we saw symptoms. Because we feared complications. But medicine isn’t about feeling right. It’s about what the data shows. The Things We Do for No Reason™ movement-started by hospitalists tired of doing things without evidence-is gaining ground. More hospitals are auditing their PPI use. More doctors are asking: Do I really need to prescribe this? And the answer, for most steroid users, is no. The American Gastroenterological Association is now reviewing its guidelines on this exact issue. A clinical trial (NCT05214345) is underway to compare ulcer rates in steroid users with and without PPIs. Results are expected in late 2024. Until then, the safest approach is the simplest: don’t treat a risk that doesn’t exist. Treat the real ones.Frequently Asked Questions

Do corticosteroids cause stomach ulcers on their own?

No, not significantly. Large studies show that corticosteroid use alone doesn’t increase the risk of peptic ulcers. Ulcer rates in people taking steroids without other risk factors are very low-around 0.4% to 1.8%. Symptoms like bloating or nausea are common but rarely mean actual tissue damage.

Should I take a PPI if I’m on prednisone?

Only if you’re also taking an NSAID like ibuprofen or naproxen, or if you have a history of ulcers, are on blood thinners, or are hospitalized. For most people taking steroids alone, PPIs offer no benefit and carry risks like C. difficile infection, low magnesium, and bone loss.

What are the real warning signs of a steroid-related ulcer?

Vomiting blood, passing black or tarry stools, sudden dizziness, pale skin, or rapid heart rate. These signal bleeding, not just irritation. If you have any of these, seek medical help immediately. Mild stomach discomfort or bloating is not a red flag.

Can H. pylori cause ulcers in people on steroids?

Yes. H. pylori is the leading cause of peptic ulcers, regardless of steroid use. If you’ve never been tested, ask your doctor. Treating this infection is far more effective than taking a PPI for prevention. Steroids don’t cause ulcers, but they can make healing slower if an infection is present.

Is it safe to stop my PPI if I’m on steroids but not on NSAIDs?

Yes, and it’s often recommended. Studies from Johns Hopkins and the University of Wisconsin show no increase in ulcers or bleeding when PPIs are stopped in steroid-only patients. Always talk to your doctor first, but if you’re not on NSAIDs or other risk factors, discontinuing your PPI is safe and may reduce side effects.

9 Comments

Honestly, this is the kind of post that makes me want to hug a doctor. We’ve been brainwashed into thinking every little ache means a pill is needed. PPIs for steroids? More like PPIs for fear. I’ve seen people on them for years and wonder why they’re always bloated or tired. Time to stop treating symptoms like diagnoses.

This is why medicine is a cult. You think you’re being rational but you’re just following the herd. PPIs are a $10 billion industry. Who’s gonna admit they’ve been poisoning people for 30 years? The fact that Hopkins and Wisconsin cut PPIs and nothing blew up? That’s not science-that’s a miracle.

Let me be crystal clear: prescribing PPIs to steroid users without concomitant NSAIDs, prior ulcer history, or anticoagulant use is not just inappropriate-it is malpractice by omission of evidence. The American College of Gastroenterology guidelines are clear. The data is unequivocal. The fact that this even needs to be debated reflects a systemic failure in clinical education and institutional inertia. We are not saving lives-we are creating iatrogenic harm.

Bro, you just wrote a 2000-word essay to say 'don't take PPIs unless you're on ibuprofen'. I get it. But why does every medical post have to be a thesis? I'm on prednisone for my lupus and I take omeprazole because my stomach feels like it's being eaten by a bear. Your data doesn't fix that.

I can’t believe Americans are still arguing about this. In Europe, they’ve known for years this is nonsense. We don’t hand out PPIs like candy. You people treat your stomachs like they’re fragile porcelain dolls. Grow a spine. And stop blaming doctors for your anxiety.

The real tragedy here isn’t the PPI overuse-it’s the epistemological laziness of modern medicine. We’ve replaced epistemic humility with algorithmic protocol. The fact that a 2013 review was ignored for a decade speaks volumes about the institutional capture of clinical practice by pharmaceutical incentives. We are not healing-we are optimizing for billing codes.

I’ve been a nurse for 18 years and I’ve seen this play out a hundred times. Patients come in scared because their stomach feels 'off' after starting steroids. We check for H. pylori, review meds, and most times-it’s just gas. I’ve had patients cry because they thought they had a bleeding ulcer. Turns out, they just ate too much pizza. This post? It’s the kind of clarity we need more of. Thank you.

So let me get this straight. You’re telling me I don’t need a PPI if I’m on prednisone but I’m also on coffee, stress, and 3 kids screaming at 5am? Cool. My stomach’s gonna be fine then. Meanwhile, my doctor’s still writing the script because he’s scared of getting sued. You’re right. But nobody’s gonna change until someone gets sued.

LMAO at the 'alarm symptoms' list. Vomiting blood? Black stools? Bro, if you’re seeing that, you’re already in the ER. The real alarm symptom is your doctor still prescribing PPIs like they’re vitamins. Also, H. pylori? Test for it. But also, maybe stop eating Taco Bell every night. Just saying.