DPP-4 Inhibitor Pancreatitis Risk Calculator

This tool helps you understand your individual risk of developing pancreatitis while taking DPP-4 inhibitors based on your medical history. According to a 2024 study in Frontiers in Pharmacology, patients on DPP-4 inhibitors have a 13.2x higher reporting odds ratio for acute pancreatitis compared to other diabetes drugs.

The absolute risk is low (about 0.13% higher), but pancreatitis can be serious. This calculator helps you weigh your individual risk factors.

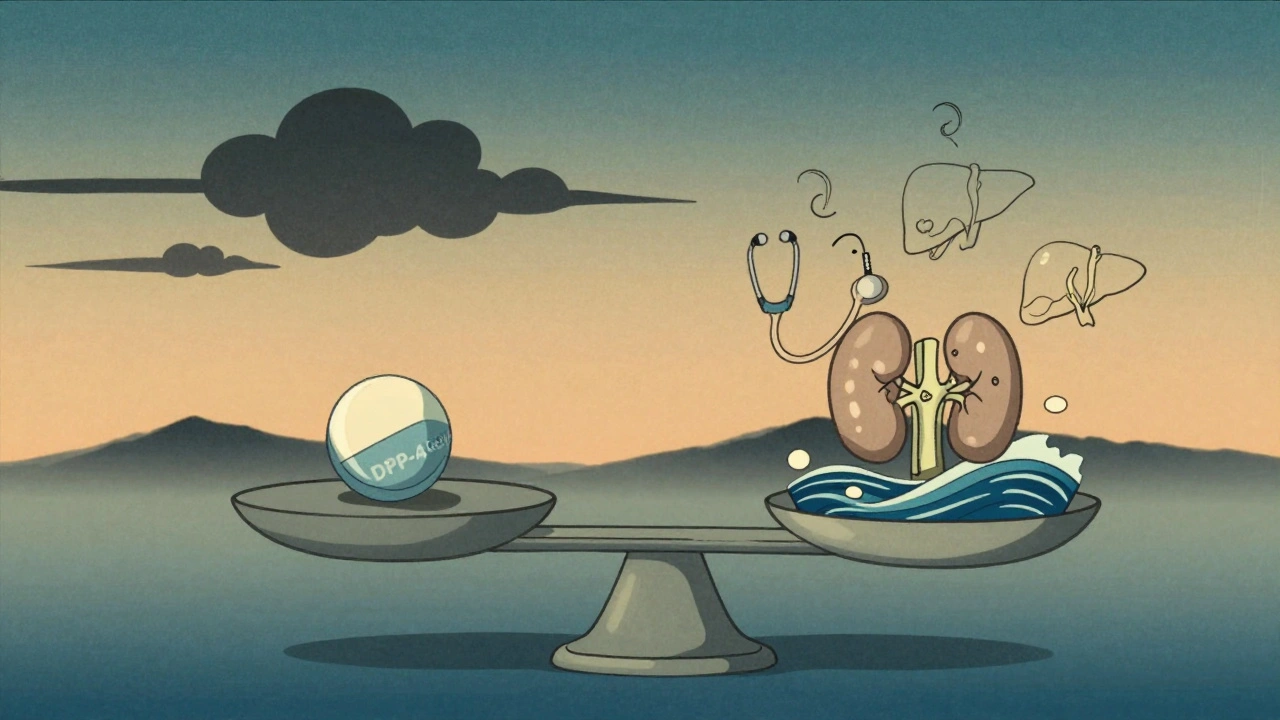

When you're managing type 2 diabetes, finding a medication that lowers blood sugar without causing weight gain or low blood sugar is a big win. That’s why DPP-4 inhibitors-also called gliptins-became so popular. Drugs like sitagliptin (a DPP-4 inhibitor used to treat type 2 diabetes by enhancing insulin release and reducing glucagon, Januvia), saxagliptin (a DPP-4 inhibitor approved in 2009, often prescribed with metformin, Onglyza), and linagliptin (a DPP-4 inhibitor excreted mostly through bile, not kidneys, making it useful for patients with kidney disease, Tradjenta) were marketed as safe, simple, and effective. But behind the convenience lies a quiet but serious risk: acute pancreatitis.

Pancreatitis Isn’t Just a Rare Side Effect-It’s a Real One

It’s easy to dismiss pancreatitis as something that happens to heavy drinkers or people with gallstones. But studies now show that even people with no history of alcohol abuse or gallbladder issues can develop it after taking a DPP-4 inhibitor. The data doesn’t lie. A 2024 study in Frontiers in Pharmacology found that patients on DPP-4 inhibitors had a reporting odds ratio (ROR) of 13.2 for acute pancreatitis compared to other diabetes drugs. That means the chance of reporting pancreatitis was over 13 times higher in people taking these drugs. The absolute risk is still low-about 0.13% higher than those not taking them. That translates to roughly one extra case of pancreatitis for every 834 patients treated for two and a half years. But when it happens, it’s not mild. Symptoms include sudden, severe pain in the upper abdomen that often radiates to the back, nausea, vomiting, and fever. Some patients end up in the hospital. About 17.7% of reported cases were classified as serious. The UK’s Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) confirmed this in 2012, and since then, every major regulatory body-including the FDA and EMA-has updated the labels of all DPP-4 inhibitors to include pancreatitis as a potential side effect. What’s more, these cases didn’t just pop up in post-marketing reports. They showed up in large clinical trials, too. The CVOTs for saxagliptin, alogliptin, and sitagliptin all showed more pancreatitis cases in the drug group than in the placebo group, even if the numbers weren’t always statistically significant. Why? Because pancreatitis is rare, and these trials weren’t designed to catch it. But the pattern was clear enough to trigger action.Why Does This Happen? We Still Don’t Fully Know

Here’s the frustrating part: scientists still don’t know exactly how DPP-4 inhibitors trigger pancreatitis. The enzyme DPP-4 breaks down incretin hormones like GLP-1, which helps regulate blood sugar. Blocking it increases GLP-1 levels-that’s the whole point. But GLP-1 is also present in the pancreas. Animal studies have been all over the place. Some showed inflammation, others didn’t. Human tissue samples haven’t revealed a consistent mechanism. One theory is that increased GLP-1 may cause pancreatic cells to grow or become more active, leading to stress or inflammation. Another idea is that DPP-4 inhibitors affect immune cells in the pancreas, triggering an inflammatory response. But none of these have been proven. What we do know is that diabetes itself raises your baseline risk of pancreatitis. So when someone with type 2 diabetes takes a DPP-4 inhibitor, they’re already at higher risk than a healthy person. The drug may be pushing them over the edge.How Do DPP-4 Inhibitors Compare to Other Diabetes Drugs?

It’s not just DPP-4 inhibitors. GLP-1 receptor agonists like liraglutide and semaglutide have also been linked to pancreatitis-but less strongly. The same 2024 study showed a ROR of 9.65 for GLP-1 agonists, compared to 13.2 for DPP-4 inhibitors. That means while both carry risk, DPP-4 inhibitors appear to be more strongly associated with pancreatitis reports. On the other hand, SGLT2 inhibitors-drugs like empagliflozin and dapagliflozin-have a significantly lower rate of pancreatitis. In fact, they’re often recommended as alternatives for patients with risk factors for pancreatitis. SGLT2 inhibitors also offer extra benefits: they reduce heart failure risk and slow kidney disease progression, which DPP-4 inhibitors don’t. And here’s something important: despite the pancreatitis risk, DPP-4 inhibitors do not increase the risk of pancreatic cancer. A major 2017 meta-analysis of over 55,000 patients found no link. That’s a relief, because early fears about cancer were widespread. But that doesn’t make pancreatitis any less dangerous.

Who’s Most at Risk?

Not everyone on a DPP-4 inhibitor will get pancreatitis. But some people are more vulnerable:- People with a history of pancreatitis, even if it was years ago

- Those with gallstones or high triglycerides

- Patients who drink alcohol regularly

- People with obesity

- Those taking multiple medications that stress the pancreas

What Should You Do If You’re Taking a DPP-4 Inhibitor?

You shouldn’t stop your medication without talking to your doctor. But you should know the signs and act fast:- Pay attention to abdominal pain-especially if it’s severe, constant, and doesn’t go away after eating or taking antacids.

- Watch for pain that moves to your back.

- Notice if you’re vomiting, feeling nauseous, or have a fever with no other cause.

- If you experience any of these, contact your doctor immediately. Don’t wait.

- Your doctor may order blood tests for amylase and lipase (pancreatic enzymes) and an ultrasound to check for gallstones or inflammation.

Are DPP-4 Inhibitors Still Worth It?

Yes-for many people. They’re weight-neutral, don’t cause low blood sugar (unlike sulfonylureas), and have a strong safety record for the heart. That’s why the American Diabetes Association still lists them as a recommended option in their 2023 Standards of Care. In 2022, they made up about 15% of all oral diabetes prescriptions in the U.S., with sitagliptin being the most prescribed. But “recommended” doesn’t mean “risk-free.” It means the benefits outweigh the risks-for most. If you’re a 65-year-old with well-controlled diabetes, no gallstones, no history of pancreatitis, and no alcohol use, the chance of harm is very low. But if you’re a 50-year-old with high triglycerides, a history of gallbladder issues, and occasional weekend drinking? The risk may not be worth it.

What Are Your Alternatives?

If your doctor is concerned about pancreatitis risk, here are other options:- SGLT2 inhibitors (e.g., empagliflozin, dapagliflozin): Lower blood sugar, help the heart and kidneys, and have lower pancreatitis risk.

- GLP-1 receptor agonists (e.g., semaglutide, liraglutide): More effective at lowering blood sugar and promoting weight loss, but carry a small pancreatitis risk themselves.

- Metformin: Still the first-line drug for most people with type 2 diabetes. Low cost, low risk, proven over decades.

- Insulin: If other drugs aren’t working, insulin remains the most reliable option.

Reporting Side Effects Matters

If you or someone you know develops pancreatitis while on a DPP-4 inhibitor, report it. In the UK, use the Yellow Card scheme. In the U.S., report to the FDA’s MedWatch system. These reports help regulators spot patterns and update safety guidelines. The more data we have, the safer prescribing becomes.What’s Next?

Researchers are now looking for genetic markers that might predict who’s more likely to develop pancreatitis on these drugs. If we can identify high-risk patients before they start, we can avoid the problem entirely. Until then, awareness is your best defense. DPP-4 inhibitors aren’t going away. They’re still useful. But they’re no longer the “safe bet” they once seemed. Knowing the risks, recognizing the symptoms, and talking to your doctor about alternatives isn’t being paranoid-it’s being smart.Can DPP-4 inhibitors cause pancreatic cancer?

No, current evidence shows DPP-4 inhibitors do not increase the risk of pancreatic cancer. A large 2017 meta-analysis of over 55,000 patients found no link between these drugs and cancer, despite early concerns. The main risk is acute pancreatitis, not cancer.

What are the most common side effects of DPP-4 inhibitors?

The most common side effects are mild: headaches, stuffy or runny nose, and sore throat. These are usually temporary. Serious side effects like pancreatitis are rare but require immediate attention if symptoms appear.

Should I stop taking my DPP-4 inhibitor if I have mild stomach pain?

Don’t stop without talking to your doctor. But if you have persistent, severe abdominal pain-especially with vomiting or back pain-contact your doctor right away. Mild discomfort could be something else, but severe pain could signal pancreatitis. It’s better to get checked than to wait.

Are DPP-4 inhibitors safe for people with kidney problems?

Linagliptin (Tradjenta) is safe for people with kidney disease because it’s mostly cleared through the liver, not the kidneys. Other DPP-4 inhibitors like sitagliptin and saxagliptin may need dose adjustments in advanced kidney disease. Always check with your doctor based on your kidney function.

How do I know if my DPP-4 inhibitor is right for me?

Your doctor should consider your overall health: Do you have gallstones? High triglycerides? A history of pancreatitis? Do you drink alcohol? Are you trying to lose weight? If you have risk factors for pancreatitis, alternatives like SGLT2 inhibitors or GLP-1 agonists may be safer. If you’re low-risk and need a simple, weight-neutral option, DPP-4 inhibitors can still be a good fit.

8 Comments

I’ve been on sitagliptin for three years now and never had a single issue. My A1c’s been steady at 6.1, no weight gain, no crashes. I get that pancreatitis is scary, but I’ve also seen people panic over stats without context. If you’re low-risk, don’t toss a med that’s working just because of a 0.13% bump. Talk to your doc, don’t doomscroll.

This whole thing is just Big Pharma covering their ass after they sold us a miracle drug that turned out to be a slow-burn bomb. They knew. They always knew. And now they’re acting like it’s some rare fluke when it’s clearly a pattern they ignored for profit.

Man, I remember when everyone was hyping these things like they were diabetes magic beans. Now it’s like, ‘oh wait, your pancreas might hate you?’ I switched to metformin after reading this-no regrets. Cheaper, proven, and my stomach’s happier. Not saying ditch gliptins, but maybe don’t start with them unless you’re low-risk.

It’s wild how medicine keeps finding these subtle trade-offs. We want drugs that don’t cause weight gain or hypoglycemia, so we pick gliptins… and then we get pancreatitis risk. But the fact that they don’t raise cancer risk is a huge relief. Maybe the real lesson isn’t ‘avoid these drugs’ but ‘know your body’s history.’ If you’ve had even one bout of pancreatitis, you’re not the candidate for this. But if you’re otherwise healthy? It’s still a valid tool.

I’ve seen too many people swing from ‘this is the best thing ever’ to ‘never touch it again.’ Medicine’s messy. We’re all just trying to balance risk and quality of life.

Just wanted to say thanks for laying this out so clearly. I’m on linagliptin because of my kidney issues, and I’ve been nervous since reading about the pancreatitis risk. This helped me understand the numbers better-like, 1 in 834 over 2.5 years? That’s way lower than I thought. I’ll keep monitoring symptoms but feel less panicked now.

so like... gliptins cause pancreatitis? shocker. next youll tell me smoking causes lung cancer. lol. also why is everyone acting like this is new info? the label's had warnings since 2012. you guys just ignore the small print until something bad happens. classic. also sglts are better anyway so why are you even on this stuff

For anyone considering switching: if you're on a DPP-4 inhibitor and have risk factors like high triglycerides, gallstones, or past pancreatitis, SGLT2 inhibitors are a clinically superior alternative. They don’t just avoid pancreatitis risk-they reduce heart failure hospitalizations and slow CKD progression. Metformin remains first-line for most. GLP-1 RAs are great for weight loss but carry a slightly higher pancreatitis risk than SGLT2s. Always base your choice on your comorbidities, not just convenience or cost. Your pancreas will thank you.

Ugh. I had pancreatitis in 2020 after being on saxagliptin for 8 months. They told me it was ‘probably’ the drug. I’m still angry. Why didn’t they test me earlier? Why was I told it was ‘rare’? Now I’m stuck with insulin and a $300/month bill. This isn’t a ‘risk’-it’s a trap. And no, I won’t be trusting Big Pharma’s ‘safe’ labels again.