Most people think of color blindness as seeing the world in black and white. But that’s not what it usually looks like. For the vast majority of people with color vision issues, it’s not about missing colors altogether-it’s about confusing red and green. This isn’t a rare oddity. Around 8% of men and less than 1% of women worldwide have some form of red-green color blindness. It’s not a disease. It doesn’t get worse over time. And it doesn’t mean you can’t see clearly. But it does change how you interact with the world-in ways most people never notice.

Why Red and Green Are the Problem

Your eyes have three types of cone cells that detect color: one for red, one for green, and one for blue. The red and green ones are the troublemakers. Their genes are packed together on the X chromosome. That’s why this condition hits men so much harder. Men have one X and one Y chromosome. If the X they inherit has a faulty red or green pigment gene, they’re affected. Women have two X chromosomes. So even if one has the mutation, the other often compensates. That’s why only about 0.5% of women have it.The genes responsible are called OPN1LW (for red) and OPN1MW (for green). They sit side by side like train cars on the X chromosome. Sometimes, during sperm or egg formation, these genes accidentally swap pieces. That’s called unequal crossover. The result? A gene that’s half red, half green. Or worse-a gene that’s completely missing. When that happens, the cone cells either don’t make the right pigment, or they make a messed-up version. That’s what leads to the confusion between reds, greens, browns, and oranges.

Two Main Types: Protanopia and Deuteranopia

There are two main forms of full red-green color blindness. One is called protanopia. People with this condition have no working red pigment. Reds look dark, almost black. Some greens and yellows blend into the same muddy shade. The other is deuteranopia, where the green pigment is missing. This is more common. Greens look washed out. Reds appear more yellow or brown. The lines between them blur.But most people don’t have either of these full versions. About 5% of men have something called deuteranomaly. That’s a milder version where the green pigment is there-but it’s off. It doesn’t respond properly to light. Same with protanomaly, which is rarer. These people aren’t colorblind in the classic sense. They just struggle to tell apart certain shades. A red traffic light might look too orange. A green leaf might seem too yellow. They can still function fine. But they might not realize why they keep picking the wrong tie or mixing up wires in electronics.

How It’s Passed Down: The X Chromosome Rules

Let’s say a man has red-green color blindness. He passes his X chromosome to all his daughters, but none of his sons (sons get his Y). So his daughters become carriers. If a woman is a carrier, she has a 50% chance of passing the mutated gene to each child. If she passes it to a son, he’ll be colorblind. If she passes it to a daughter, the daughter will be a carrier-unless the father is also colorblind, which is rare.That’s why you see it jump generations. A grandfather might be colorblind. His daughter isn’t. But her son is. People often think it skipped a generation. It didn’t. The mother just didn’t show it. She carried it. And now her son has it.

Women can be affected, but it’s rare. They’d need to inherit the faulty gene from both parents. That means their father must be colorblind, and their mother must be at least a carrier. The odds? About 1 in 4,000. That’s why most women with red-green color blindness don’t even know they have it until they get tested.

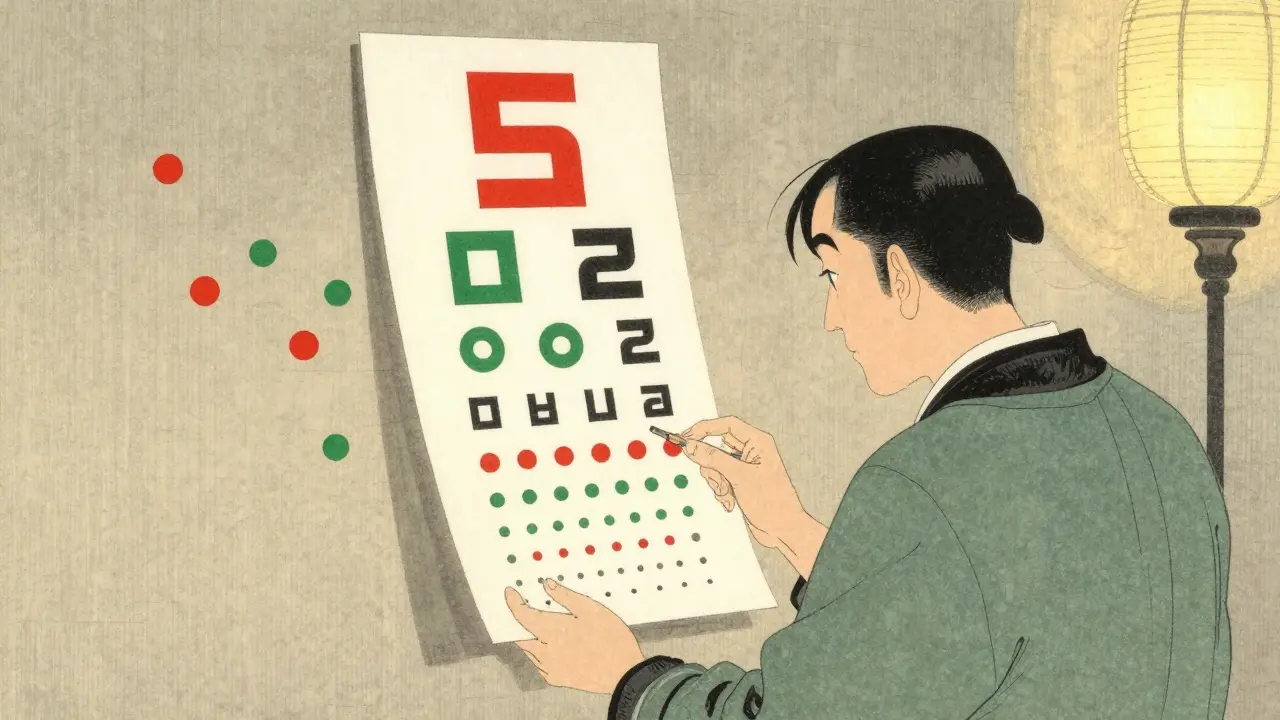

How It’s Tested: The Ishihara Plates

The most common test is the Ishihara test. It’s been around since 1917. It uses circles made of colored dots. Inside the dots, a number is hidden. People with normal color vision see a 5. Someone with red-green deficiency might see a 2-or nothing at all. It’s simple. It’s cheap. And it’s still the standard.But it’s not perfect. Some people pass the test but still struggle in real life. Others fail the test but can tell red from green just fine. That’s because the test only checks for certain types of deficiency. A more detailed test called the Farnsworth-Munsell 100 Hue Test can catch subtler issues. But most doctors still start with the Ishihara plates.

Real-Life Challenges Nobody Talks About

You might think, “So what? It’s just colors.” But color blindness affects daily life in ways most people overlook.One man, a commercial pilot applicant, was turned down because he couldn’t distinguish red and green lights on the runway. He had 20/20 vision. But he failed the color test. Another person, an electrician, told me he once wired a panel wrong because the red and green wires looked identical. He only caught it because his coworker noticed the mistake. Now he labels every wire with numbers.

Students struggle in school. Graphs with red lines on green backgrounds? Impossible to read. Teachers don’t always realize this. A survey found that 78% of people with red-green color blindness had trouble with color-coded learning materials. In classrooms, labs, and even online quizzes, color is often the only clue.

Even something as simple as choosing clothes can be awkward. One woman said she once wore a bright red shirt with a green scarf to a job interview. She didn’t realize they clashed until someone said, “That’s… an interesting combo.” She felt embarrassed. She’s since learned to use apps that show her what colors look like to others.

Tools and Tech That Help

There’s no cure. But there are tools that make life easier.EnChroma glasses cost between $330 and $500. They don’t restore normal color vision. But they sharpen the contrast between reds and greens for about 80% of users. People report seeing new shades of orange, purple, and pink. It’s not magic. But for some, it’s life-changing.

There are also free digital tools. Color Oracle is a program that simulates how your screen looks to someone with red-green deficiency. Designers use it to make websites, apps, and presentations more accessible. Apple and Windows both have built-in color filters. You can turn your screen to grayscale or invert colors to make distinctions clearer.

There’s even a system called ColorADD, used in public transit systems across 17 countries. Instead of relying on color, it uses simple shapes: a triangle for red, a square for green, a circle for blue. It’s not flashy. But it works.

What’s Next? Gene Therapy and Better Tech

Scientists are making progress. In 2022, researchers gave gene therapy to squirrel monkeys with red-green color blindness. After treatment, they could see red and green like never before-and kept that ability for over two years. That’s huge. It proves the brain can learn to process new color signals, even as an adult.Companies are also improving lens technology. EnChroma released a new version in early 2023 that works 30% better for deuteranomaly. Other startups are working on AR glasses that can label colors in real time. Imagine walking into a store and seeing “red” pop up next to the shirt you’re holding.

Regulations are catching up too. The UK’s Equality Act 2010 recognizes color blindness as a disability. Employers must make reasonable adjustments. Schools are starting to train teachers. Tech companies are updating their accessibility guidelines. The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) now require color contrast checks and non-color-dependent cues. That means websites can’t just say “click the green button.” They have to say “click the green button labeled ‘Submit.’”

It’s Not a Disability-It’s a Difference

Most people with red-green color blindness don’t see it as a handicap. A survey found that 92% consider it a minor inconvenience. Many say it’s made them more observant. They learn to rely on brightness, texture, shape, and context. A designer with deuteranomaly told me she now creates interfaces that are clearer for everyone-not just people like her.It’s not about fixing people. It’s about designing a world that works for everyone. You don’t need to see colors the same way to understand them. You just need the right tools-and a little awareness.

10 Comments

Wow, this was so eye-opening... 🤯 I never realized how much color blindness affects daily life beyond traffic lights. I used to think it was just a quirky thing, but now I see how it impacts jobs, education, even choosing clothes. I’m gonna start using colorblind simulators when designing anything for others. Thank you for sharing this.

Ugh. Another ‘it’s just a difference’ sugar-coated article. It’s not a ‘difference’-it’s a biological defect that excludes people from careers, education, and social norms. Why are we normalizing mediocrity? If you can’t see red and green, you shouldn’t be flying planes or wiring circuits. Safety first, feelings last.

Okay but let’s be real-this whole thing is a scam. The Ishihara test? Designed by a British dude in 1917. Who even trusts that? I bet the whole color blindness thing is just a corporate ploy to sell EnChroma glasses. I know a guy who passed the test but still couldn’t tell red from green… and he swears he’s got ‘color synesthesia’ from drinking kombucha. 🤷♂️

People who say it’s ‘not a disability’ are either lying to themselves or haven’t been denied a job because of it. I’ve seen it happen. My cousin was rejected from the Navy because he couldn’t distinguish red from green on radar screens. He had perfect vision otherwise. This isn’t about ‘awareness’-it’s about systemic bias disguised as ‘inclusion.’ And don’t even get me started on how schools ignore this until a kid fails a test.

As an electrician, I can confirm the wire thing is real. I had a coworker mix up a red and green wire once-almost caused a short. Now we all label everything with tape and numbers. Also, Color Oracle is a lifesaver. I use it before sending any design files to clients. Simple fix, huge impact. If you’re designing anything, test it in grayscale first. It’s not hard, and it’s respectful.

i just learned that my brother has deuteranomaly and he never told anyone… he thought everyone saw colors like him. he said he used to think the sky was ‘kinda yellowish’ and didn’t realize it was blue. this article made me cry. i’m gonna send him the color oracle link and get him a pair of enchroma glasses for his birthday. he deserves to see the world as it is. ❤️

This is a textbook example of Western medical paternalism. The Ishihara test? A colonial relic. The real issue is that color perception varies across cultures-many indigenous groups have more nuanced color distinctions than Westerners. This article reduces a complex biological and cultural phenomenon to a genetic flaw in a Caucasian male population. It’s not about ‘color blindness’-it’s about linguistic and perceptual hegemony disguised as science.

Great breakdown. I appreciate how you framed it as a difference, not a deficit. My niece has protanomaly, and we’ve started using shape-based labels on her crayons and toys. She’s 5 and already teaches her classmates how to tell red from green by brightness. It’s not about fixing her-it’s about changing how we present information. Small changes, big impact.

Wait-so you’re telling me this is genetic? That means it’s programmed into our DNA by the elites to control perception. I’ve been noticing this for years. The government uses red-green signals in traffic, apps, and even voting machines to subtly manipulate who sees what. Why do you think they never test for blue-yellow deficiency? Because they don’t want you to know how many colors you’re missing. This is mind control. I’ve been researching this since 2018. The real cure? Stop using screens. Go analog. Live in the woods. 🌲

I didn’t know I was colorblind until I was 28. I thought everyone saw the same shades I did. I wore mismatched clothes all the time. Now I use my phone’s color picker. It’s a small thing, but it changed everything.