If you have recent African ancestry, your risk for certain types of kidney disease isn’t just about diet, blood pressure, or diabetes-it’s written into your DNA. The APOL1 gene variants G1 and G2 are responsible for nearly 70% of the extra kidney disease risk seen in people of African descent. This isn’t a myth, a rumor, or a statistical fluke. It’s one of the strongest genetic links ever found to a common disease, and it’s reshaping how doctors understand kidney health.

Why APOL1 Exists: An Evolutionary Trade-Off

These gene variants didn’t appear by accident. Around 5,000 to 10,000 years ago in West and Central Africa, a deadly parasite called Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense-the cause of African sleeping sickness-was killing people. People who carried one copy of the G1 or G2 variant in their APOL1 gene were much more likely to survive the infection. Their bodies made a protein that could punch holes in the parasite’s membrane and kill it. Over generations, this survival advantage meant more people passed these variants on. Today, about 30% of people in Ghana and Nigeria carry at least one of these variants. But here’s the catch: having two copies is dangerous. When both copies of the gene carry the G1 or G2 variant-whether two G1s, two G2s, or one of each-the protein doesn’t just fight parasites. It starts attacking kidney cells. This is why these variants are so rare in European, Asian, or Indigenous American populations. They never had the same evolutionary pressure. The trade-off was clear: survive sleeping sickness, risk kidney disease decades later.Who’s at Risk and How It Works

You don’t get kidney disease just because you have one copy of the variant. You need two. That’s called a recessive inheritance pattern. Only about 13% of African Americans have this high-risk combination. But among those who develop non-diabetic kidney disease, nearly half carry these variants. That’s not coincidence-it’s the main driver. The kidney diseases linked to APOL1 aren’t the usual suspects. They’re rare, aggressive types like focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), collapsing glomerulopathy, and HIV-associated nephropathy (HIVAN). In the UK, almost half of all end-stage kidney disease cases in people of African ancestry with HIV were directly tied to APOL1, according to the GEN-AFRICA study in 2023. That’s a staggering number. And here’s the twist: most people with two high-risk copies never get sick. About 80% of them keep normal kidney function their whole lives. That’s called incomplete penetrance. So what triggers the damage? Something else-a virus, high blood pressure, obesity, or another genetic factor. These are called "second hits." That’s why someone can live a healthy life and suddenly develop kidney failure after an infection or uncontrolled hypertension.Testing and Diagnosis: What You Need to Know

Genetic testing for APOL1 became available in 2016. Companies like Invitae and Fulgent Genetics offer tests that cost between $250 and $450 without insurance. It’s not part of routine screening, but it’s strongly recommended for people of African ancestry who have kidney disease, especially if it’s not caused by diabetes or high blood pressure. It’s also required for living kidney donors of African descent. If you’re thinking about donating a kidney, testing your APOL1 status is now standard. Why? Because if you have two high-risk variants, you’re at higher risk of developing kidney disease yourself later in life. Donating one kidney could tip the balance. The results aren’t simple yes-or-no answers. A positive test doesn’t mean you’ll definitely get kidney disease. It means your risk is higher. Many patients misunderstand this. One study found that 35% of people thought a positive test meant they were guaranteed to fail. That’s not true. It means you need to be more careful.

What to Do If You Have High-Risk APOL1

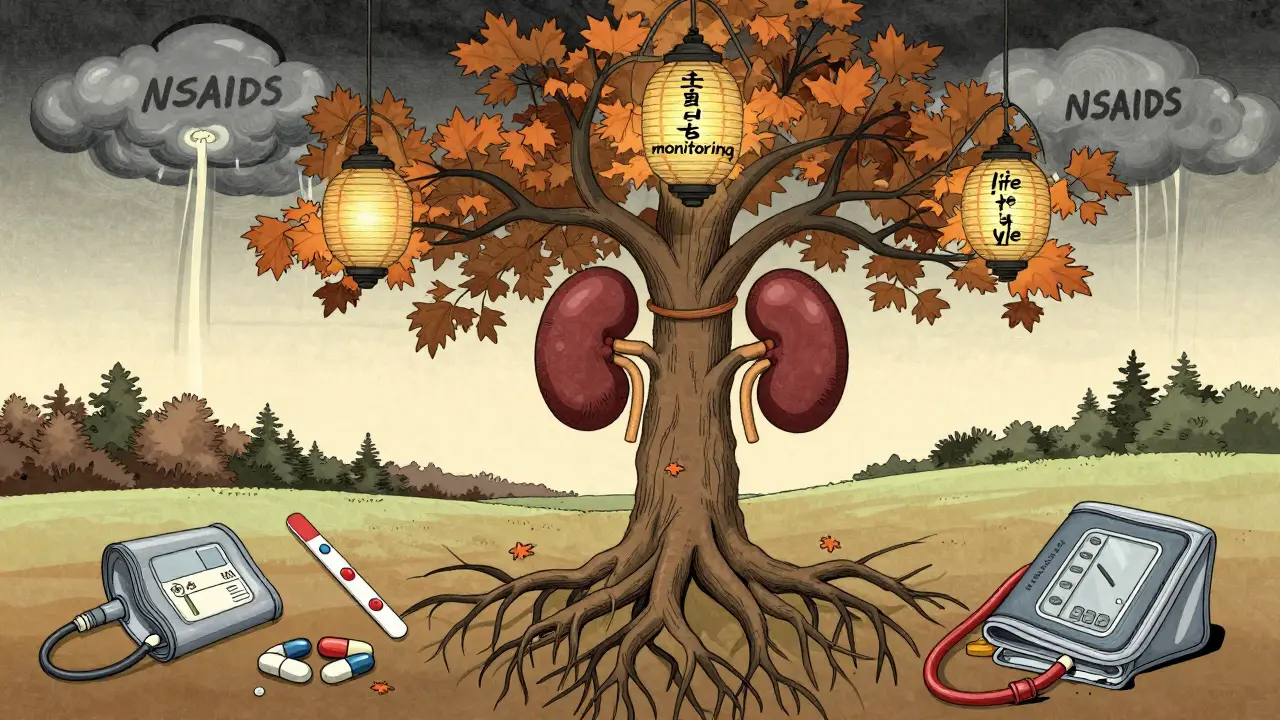

There’s no cure yet, but there are proven ways to lower your risk. The American Society of Nephrology’s 2023 guidelines are clear: if you have high-risk APOL1, get your urine tested every year for albumin (a sign of early kidney damage) and keep your blood pressure under 130/80. That’s stricter than the general recommendation. Avoid NSAIDs like ibuprofen and naproxen-they can stress your kidneys. Don’t smoke. Control your weight. If you have HIV, get it treated early and keep it suppressed. These aren’t just good ideas-they’re your best defense. Some people, like Emani from the Kidney Fund’s 2023 case study, found out they had high-risk APOL1 before any damage occurred. With regular monitoring and lifestyle changes, she’s kept her kidney function stable for over five years. That’s the goal: catch it early, act fast.Why Race Isn’t the Right Word

You’ll hear people say "Black people are more likely to get kidney disease." That’s misleading. The risk isn’t about race-it’s about ancestry. APOL1 variants are common in people whose ancestors came from West Africa. That includes African Americans, Afro-Caribbeans, and people from Ghana, Nigeria, or Senegal. It doesn’t matter what you look like or how you identify. What matters is your genetic lineage. Dr. Olugbenga Gbadegesin at Vanderbilt warns that mixing race and genetics can lead to harmful mistakes. Doctors might assume a Black patient has kidney disease because of "race," not because of APOL1. That leads to delayed testing, misdiagnosis, and worse outcomes. In fact, a 2022 survey found that 42% of patients with APOL1-related kidney disease had their symptoms dismissed as "just high blood pressure" before genetic testing.

9 Comments

Man, this APOL1 thing is wild-like nature’s double-edged sword. One copy keeps you alive from sleeping sickness, two copies and your kidneys start throwing a mutiny. I’ve seen cousins with high blood pressure blame everything except genetics, and now I get why. This ain’t just about diet or meds-it’s in the code. And the fact that 80% of folks with two bad copies never even get sick? That’s the universe messing with us. But hey, at least now we got tests. No more guessing.

i just found out my mom has the variant and she’s 62 and her kidneys are fine… so maybe it’s not as scary as they say? i’m gonna ask her doctor about the yearly urine test tho

bro this is why we need more indian doctors studying african genetics. we got our own issues with diabetes and kidney stuff but this is next level science. respect.

As a medical researcher from India, I find this genetic insight profoundly significant. The evolutionary trade-off between infectious disease resistance and late-onset organ vulnerability is a recurring theme in human genomics. The APOL1 variant exemplifies how natural selection operates on population-specific pressures. Yet, the clinical translation remains uneven across global healthcare systems.

This is hope. Not fear. Knowing means you can act. My cousin got tested after her creatinine went up-turned out it was APOL1. She started watching her BP, stopped ibuprofen, and now she’s fine. No dialysis. No panic. Just smart choices. You can’t change your genes, but you can change how you live with them. Keep going.

Wait-so you’re telling me that because my great-great-grandmother was from Nigeria, I’m somehow genetically programmed to have kidney failure at 50? But my uncle, who eats fried chicken every day, drinks soda, and never exercises, is fine at 70? And the guy who runs marathons and eats kale? He’s the one who got diagnosed? And you want me to believe this is all about genes and not… I don’t know-environment? Or maybe the medical system just wants to sell more tests? I mean, if it’s recessive, why are we treating it like a death sentence? And why are we blaming the gene and not the healthcare disparities that delay diagnosis until it’s too late? And why is this only being studied now, in 2024, when Black people have been dying from kidney disease for decades? And why are pharmaceutical companies already lining up to sell drugs for it? And why are we calling it a "genetic risk" and not a systemic failure? And why does no one talk about how poverty, stress, and lack of access to care are the real triggers? And why is this being framed as a biological inevitability instead of a social injustice? And-

So let me get this straight-Black people have a gene that makes them more likely to die from kidney disease? That’s not genetics, that’s a liability. We should be screening everyone with African roots before they even get a driver’s license. No one’s asking for a free pass. But if you know you’re carrying this, you should be held responsible. Don’t smoke. Don’t get fat. Don’t ignore your BP. This isn’t racism-it’s biology. And if you’re too lazy to manage it, don’t blame the system.

They’re hiding something… the APOL1 test is expensive, but the drug VX-147? It’s going to cost $200,000 a year. And who gets it? People with insurance. Who doesn’t? Black communities. And the NIH poured $125 million into this? That’s a fraction of what they spent on COVID boosters. This is a slow genocide disguised as science. They found the gene, they didn’t fix the system. They want you to think you’re broken, not that the world is. They’ll test you, scare you, then sell you a pill you can’t afford. Wake up.

It’s fascinating how the article conflates ancestry with race, as if the two are interchangeable. APOL1 is a population-specific variant, not a racial one. Yet the media continues to use "Black" as a biological category, which is both scientifically inaccurate and socially dangerous. The real issue isn’t the gene-it’s the persistent conflation of genetic ancestry with racial identity in clinical discourse. This is why medicine still fails marginalized groups: because it refuses to think in terms of population genetics and instead clings to outdated, socially constructed categories.